Many women practice their art secretly. Emily Dickinson had fewer than 12 poems published in her lifetime until her sister Lavinia discovered 1800 of them in a locked chest after she died. Jane Austen was first published anonymously.

Collecting is also an art. To do it well, you must have an encyclopedic knowledge of the culture, history, and, if signed, the artists who made objects of significance. Only then are you able to pick the best things, which are historically correct.

I know women comb collectors whose life commitment was total, scholarship voluminous, but who never published, photographed or catalogued their work. I do not feel alone in saying I’d like to change that. Therefore, it is a pleasure for me to present a few pieces from The Frances Wright Collection.

कंघी

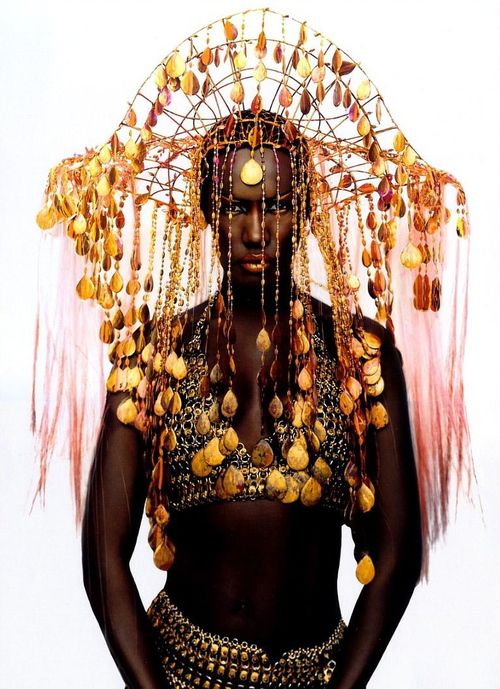

Victorian England was sublimely influenced by foreign cultures. For example, the French conquest of Algeria between 1830 and 1847 sparked an interest in the Islamic art of North Africa. The Algerian knot, looped chains, tassels, and pendants started to appear in hair combs. Called the Peigne d’Alger, the style is also known as Victorian Algerian.

This comb has three metal flowers on the tiara, which are decorated with black beads. Three black-beaded pendants of different lengths hang beneath the middle flower. Dangling from the outer flowers are two tassels and two other pendants. The final pendant hangs from the middle tassel. The entire decoration is hinged to a horn comb.

This Peigne d’Alger has an open metal frame, which holds 5 faux pearls with a smaller one attached underneath. The three middle pearls are surrounded by tassels and circles of seed pearls. Connecting chains and pendants of individual pearls hang from the 5 pearls in the frame. What makes this balance is how the different sizes of pearls are mixed. This decoration is also attached to a horn comb.

When I first saw this Peigne d’Alger, I called it a waterfall of pearls. Five faux pearls are attached to each side of one metal horseshoe-shaped fitting. The end-stubs that hold them are a part of the design. A larger pearl sits on top. The decoration is hinged to a horn comb.

A brass frame with a bow in the center, two holes on the edges, and diagonal lines in the center supports a geometric design of cords with gold rings to hold them in place. In this Peigne d’Alger, the cords end in hinges, which go through the brass diagonal pieces. Small brass pendants dangle from them. On the bottom are three larger rock-crystal pendants. The frame is attached to a horn comb.

The Victorians loved sterling silver combs. This one, with flowers surrounded by garlands, dates to 1880.

Victorian tortoiseshell hair pins with gold tops were a frequent part of a woman’s wardrobe. However, finding one with a circular top is rare.

In France, Napoleon’s first queen, Josephine, was a jewelry innovator. Her style of back comb, which can also be worn as a tiara, is called a Peigne Josephine. It has a brass comb upon which multi-galleried decorations are attached. Coral was a favorite jewel, as were seed pearls.

This Peigne Josephine has 5 galleries: a line of seed pearls, metal mounted with seed pearls, another row of seed pearls, metal in a leaf pattern, and on top spirals of seed pearls. The pearls are wound on very thin wire, so the condition and is remarkable.

This French comb has meticulously painted porcelain medallions of courtly scenes on metal with three tassels, hinged to a horn comb. The medallions are reminiscent of 18th Century French furniture.

This comb is an Art Deco extravaganza. It is a celluloid comb made at the comb factories in Oyonnax, c. 1920. A small geometric pattern builds to diamond-shaped purple rhinestones to flowers to purple and orange arches at the top. Unbelievably, this is unsigned.

This American Civil War Era garnet tiara has a four-petaled flower, shouldered by two leaves, and is attached to a tortoiseshell comb. The leaf-stems in the middle are comprised of larger garnets. There are two 3/4 circular pieces, which I believe attach to the tiara. One can see hinges at the bottom of the leaves and on each piece. Quite unique.

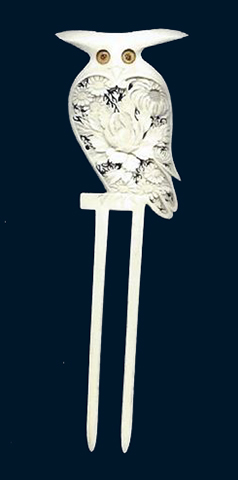

I had never seen Chinese embroidered flower carvings inside an owl before this ivory hair pin. It is beautifully carved in the Cantonese tradition. The owl even stares back at you. c. 1890, made for export.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine our Resource Library and these books:

The Comb: Its History and Development |

Combs and Hair Accessories |

Hair Combs: Identification & Values |