The Museum Showed the Comb Upside Down

History is rarely told by the vanquished. If we find their story, we who live in the world of the conquerors don’t know how to read it. We highlight a big ship as the central character in an artwork, as did The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

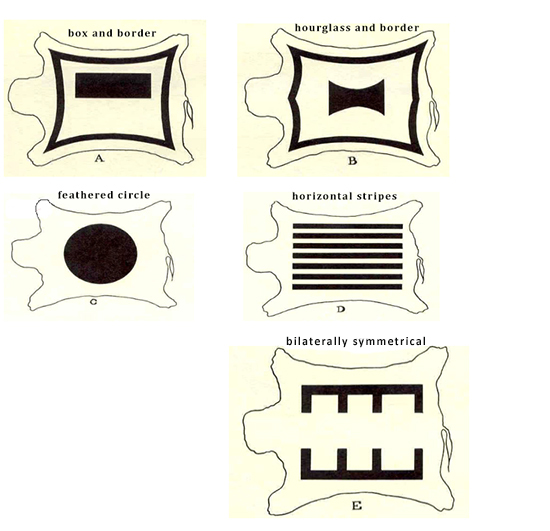

Native people in the Plains had five categories of geometric design, mostly used on decorative robes: the box and border, the hourglass and border, the bilaterally symmetrical, the horizontal stripes, and the feathered circle.

Through trade, it is possible that the bilaterally symmetrical pattern, favored by the Lakota Sioux of North Dakota, came down from the Inupiaq of Alaskan Bering Sea. The Inupiaq use their bilaterally symmetrical writing system on this comb, c. 1840 – 1890: two-dimensional pictographs and petroglyphs organized in vertical sections, with a set of two horizontal lines in composite perspectives — the bottom, right-side up, and the top, upside down.

However, unlike the way the San Francisco museum shows this comb, the ship should be upside down, because its story is a documentary about battle, despair, the loss of self, and defeat. Blood makes the bottom geometric pattern red.

The comb correctly shown. It was made c. 1840-1890, a turbulent period in American history: Little Bighorn (1876), Wounded Knee (1890).

Before American commercial whaling, Inupiaq culture depended on subsistence whaling and walrus hunting; a traditional religion with shamans and spirit masks; ships called umiaks, which carried up to 15 people and a ton of cargo; ice fishing; and dog sleds. The whaling ships were followed by Protestant missionaries, who converted everyone to Christianity in 10 years (1890-1900).

The ivory amulet on the right shows a man ice fishing. You can see the fish under water.

an umiak

By 1892, commercial whaling had destroyed the culture by employing Inupiaq hunters to work for them and kill whales on an industrial scale. They became a low-wage labor force. Diseases spread. Their traditional religion of ceremonies and dream spirits had disappeared. The church destroyed their language by teaching scrimshaw artists to draw in a three-dimensional realistic Western style.

This model of a New England whaling ship was made, c. 1850.

The comb portrays this story in the traditional language.

From the top:

Section 1: The top row (upside down) shows dog sledding. The second row (right-side up) looks like life in the village.

Section 2: First row (upside down) portrays an American whaling ship — the root of this culture’s destruction. The second row (right-side up) portrays an umiak — a large open skin-boat, which was used for hunting whale and walrus, and for trading voyages. Most of these boats were 15-20 feet long. They were constructed by lashing seal skins to a wooden frame. Fifteen people and a ton of cargo could fit comfortably.

Section 3: Both rows show a battle between sailors and villagers that ends in defeat, hence the blood on the bottom, almost making the geometric pattern a fourth section.

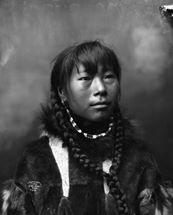

As for the comb’s use, the fact that there are tines on both sides favors utilitarian tasks, such as combing hair, combing skins, combing out lice, or preparing elaborate hairdos. One example has a bun at the back, with two braids folded over the ears and joining the knot behind.

Woman with an elaborate braided hairstyle

Because of the rarity of perspective, disappeared language, concise storytelling, traditional materials, and blood at the end, this comb is a masterpiece and a miracle of survival.

कंघी

References:

Sivuninga Sikum (The Meaning of Ice) |

Arctic ivory |

Carving Life |