Their faces look inside a perfect stillness.

It is the one who looks, who gives a doll their imagination.

Provenance gives them their history.

As I looked around the dining room,

Miniature clothes were embroidered in silver and gold.

Blue velvet dresses provided a backdrop for blonde curls.

A pink feathered hat adorned one, whose eyes were untouchable

A face that will never see horror,

A life that will never be defiled.

There is no memory inside a doll.

And so it was that surreality took me to a special house for a glatt-kosher dinner: the house of a doll collector.

She chose each one with meticulous care over 40 years, having owned an antiques shop and been a dressmaker. Her Galateas were placed elegantly on pedestals. They were either outside on display, or inside glass cabinets, grouped with the thought of how the viewer’s eye would move from unharmed face to perfect hand.

When I ate her food, an undiscovered identity emerged from a past life I never connected with before, in the shtetls of Russia, before my family escaped the Cossacks and came to America. This is what my ancestors must have eaten. This is who I must have been 120 years ago. America’s gift of individual freedom to pursue happiness was not known in that food. The American Dream is an identity revolution. It changes you. You become your own poem.

She showed me the pictures of her and her husband when they were young and just married, 58 years ago. How stunningly handsome they were.

The house shined with the perfection of their commitment to each other. A magnet that attached a piece of paper to the refrigerator said, “When we stand, we stand for Israel.” I immediately recognized this collection was a work of love over a lifetime and was given the honor to come back and take pictures.

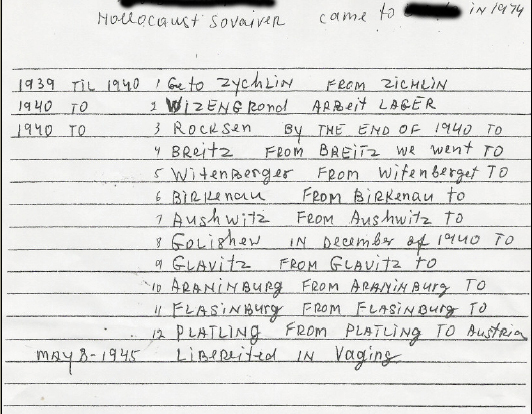

Then I learned the secret: Her husband was a Holocaust survivor, who was suffering with Alzheimer’s disease. Before his memory went away too much, he wrote down his history of a life defiled, of unimaginable horror. Stunned, you read his child-like script.

When he arrived at Auschwitz, he was standing in a line of naked men, facing Mengele, who was gesturing people to the right (life) or to the left (death). Mengele directed him to go left, while his friend went to the right. So he spoke up. “I’m young and strong. I can work. I want to be with my friend.” So Mengele said, “OK, go to the right.”

She confronted her family and convinced them to take the last train out of Krakow. When he got out of the camps, he weighed 80 pounds. So when he married her, she…

cooked food like this…

for him…

for 58 years.

And when Alzheimer’s disease tells his lungs to forget how to breathe, he will not die alone — this proud Orthodox Jew 14 German death camps couldn’t kill. He will die with the dignity of a man having felt and eaten true love — in her arms, surrounded by the beauty of the world she made for him with her dolls — unharmed, as they look perfectly, eternally into the silence.