The boundaries of the Ottoman and Persian Empires often overlapped over the course of history Their art has been enriched by many outside influences such as Central Asian, Indian, and even Chinese. Qajar is a Turkish word meaning people who walk quickly. Qajars were a Turkish-speaking minority with pastoral and nomadic lives based in Northern Persia. From the 18th to the beginning of the 20th Century, they established a dynasty, which produced a wonderful culture.

As Islam spread across through Central Asia and the Middle East, it’s not at all surprising to find images of Islamic riders with turbans on hair combs. The art of the miniature lives on this Ottoman piece, which depicts an aristocratic game of polo. Note the qualities of the drawing with its elegant, precise lines and vivid colors.

This other Ottoman comb depicts more polo players, but this time in a more stylized way. The comb itself is of camel bone, made of 4 or 5 panels stuck together to form a flat surface.

The court scene shows guests, with a glass in hand, sitting around a dish of fruit and jugs of wine.

This comb shows a scene symbolizing the pleasures of life. a smiling young woman sitting beside two musicians, offers a delicacy to the man.

Going from left to right, this comb depicts a pair of lovers. Beside them are their servants, who are cooking, while a young girl is dancing to the rhythm of a tambourine. Musical instruments, jugs of wine, and fruit are recurrent motifs because they evoke a heavenly life. These combs were probably worn by men.

Calligraphy is a very important kind of decoration, too, because writing is linked to the Koran. A Koranic verse, painted or carved, gives a talismanic quality to any object, so such a comb had a protective power, and the owner received its benefits each time he combed his hair.

For many Muslims, calligraphy is not only an art form, but also a meditative action and an act of devotion. Persian calligraphy can take various forms and styles, always ornate and complex. Here, downstrokes and upstrokes develop elegant scrolls covering the surface of the comb. To read the letters, the comb has to be held upside down.

As men turned their attention to their own appearance, elaborate mirrored storage cases came with these combs. They were made of brocade or of wood marquetry. The cases attempted to celebrate the beauty of the world, which is a reflection of heaven. The central motif on this one is called Mahi. It is a dark, diamond-shaped medallion elongated by pendants. This pattern can be seen on many carpets, especially on the city of Tabriz.

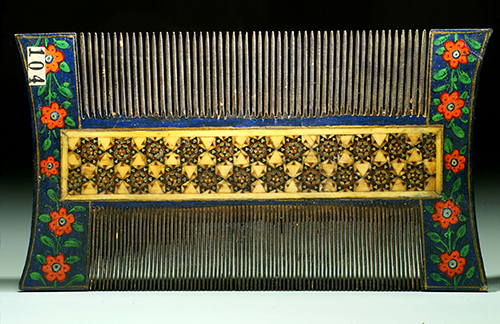

A traditional mosaic that adorned combs and boxes had incrustation work, which was called khatam kari. This art form was typically made in Shiraz and Isfahan and has been appreciated since the Safavid period. The craftsman imagines a star-shaped design, then he assembles and glues together copper, gold, or silver, rods; sticks of different types of wood; and ivory or or camel bone. Each stick has a delta-shaped cross section in order to form a cohesive unit that matches the wanted design. The cylinder is then cut into thin slices, and the sections are then ready to be plated and glued to the object ready to be decorated.

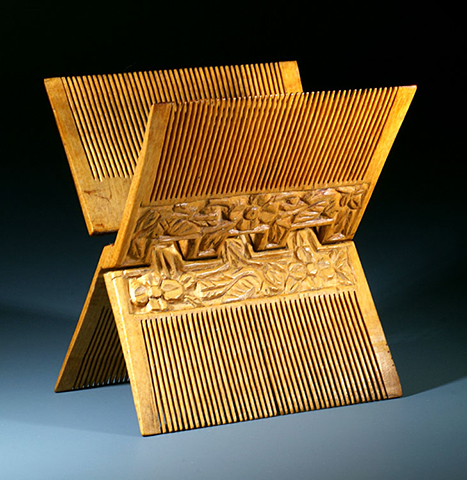

Wood carving is another type of comb also drawing on traditional methods. Two hinged X- shaped panels are cut out from a single piece of wood, then decorated with carved flowers and birds. This type of comb evokes the carved wooden Koran stands used for teaching and praying. Similar stands can also be seen in Armenian churches.

Our exhibition ends with an allegory of love: the famous motif the rose and the nightingale, Gol o Bulbul. This decoration spread throughout Persia and flourished during the Qatar Dynasty. It is still active in modern-day Iran. This miniature is a good example of Persian refinement imbued with poetry.

Poetry’s link to the Iranian people’s spirituality, where each daily gesture is sanctified. Studying hair combs has allowed us a glimpse of the Iranian patrimony. Its persisting traditions open doors to a large culture able to delight all art lovers.

कंघी

The full exhibit is available in French and English at the Creative Museum