Like a nomad gazing at the night sky, a ceiling of stars covered the main room of the 2014 exhibition, Berber Women of Morocco, at the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves St. Laurent in Paris. Each tribe’s jewelry and costume was sumptuously presented.

The accompanying book, with pages of orange and indigo-blue, is a tribute to women as the keepers of Berber, or Imaziɣn languages and traditions. (Imaziɣn means free-born.)

However, focusing on women distracts the audience from asking questions. The book is propaganda by omission: coffee-table scholarship, which veils the political confrontation upon which Berber identity depends.

A wedding necklace from the Souss area, which is made of amber, coral, amazonite shells, and pearls

The exhibition “is under the high patronage of Mohammed VI, King of Morocco,” whose mother is Berber. The King has gone out of his way to show sympathy for the Berber cause, as long as it was not political. Would it were that keeping culture alive were not political.

In 2011, the King spoke of “the plurality of the Moroccan identity, united and enriched by diversity… at the heart of which stands the Amaziɣ culture…” when Pierre Bergé opened the Musée Berbére at the Jardin Majorelle in Marrakech.

The Marjorelle Gardens, Marrakech

The Marjorelle Gardens, Marrakech

With courage, the King walks a thin line. Subordination to Arab monocultural demands is enforced all over Africa. The Arab identity and classical language are being imposed on ethnic groups of all colors, from Morocco to Sudan, even though they are already believers of Islam.

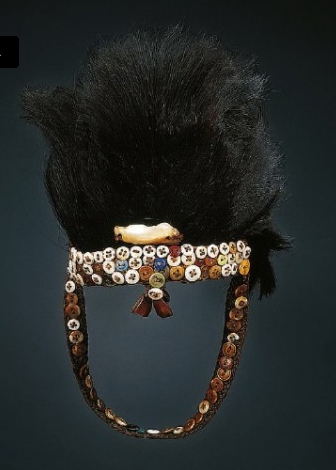

Head ornament made of flat-hanging pendants attached to a flat braided chain. From the Anti-Atlas Mountains.

In 2000, noted scholar Mohamed Chafik wrote the Berber Manifesto, signed by 229 prominent intellectuals. It accused their Arab compatriots of “ideological hegemony aimed at ethnocide,” and demanded political recognition of the Berber language as well as control of the Berber historical narrative. King Mohammed VI established the Royal Institute of Amaziɣ Culture and appointed Chafik as its dean. Another thin line?

What makes the Berber Manifesto so extraordinary is that it had no wish to return to an idealized golden age, even though the Berbers are the oldest inhabitants of Northern Africa. However, I feel Berber Women of Morocco does make this attempt, because declaring love for a moribund culture is less threatening to fundamentalist, Arabist politics. For example, Prof. Chafik would never be mentioned in a book about women, which is why this book is about women.

Beni-Sibh woman’s costume, Southeast Morocco. They were Jewish and lived in a fortified mellah, or Jewish quarter.

However, I have to give the book credit for mentioning the economic consequences of globalization, which has made it impossible for Berber women to use Morocco’s natural resources to make traditional textiles. Synthetic clothes and blankets are cheaper, easier to maintain, and sell to tourists.

Today, women even call the polyester fleece worn under their hijabs “cashmere.” Men sit at large looms in public, weaving nothing like the textiles women used to make in their homes.

Ayt Atta woman’s cape, or tamizart, made of wool and cotton

In the last chapter, Titouan Lamazou and Karen Huet wrote that 20 years ago, “this craft remained so degraded that only the most senior weavers remained.” Young weavers worked in guilds (not exactly a nomadic concept, but it’s all people can do now). “They were day laborers, kept in poverty by the masters, reluctant to pass on their knowledge” because these guilds could not maintain a stable labor force. A few decades earlier, weavers’ social status was as high as silversmiths’. So people who want to do something create more guilds where they hope people will stay, and knowledge can be transferred.

Woven women’s belts

Yet in the foreward, Pierre Bergé said, “Proud of their heritage, the Imaziɣn are ready to face the present, convinced as I am, that civilization is nothing more than a respect for the past while welcoming the future.” I never knew anyone who welcomed a future of globalization with a fake identity imposed upon them.

The Berbers are in a political fight between Arabism and pluralism. Arabism = ethnocide; pluralism = survival. Chafik is right. I just wish the book could have included this, so people would understand why the Berbers weren’t in charge of their own exhibit.

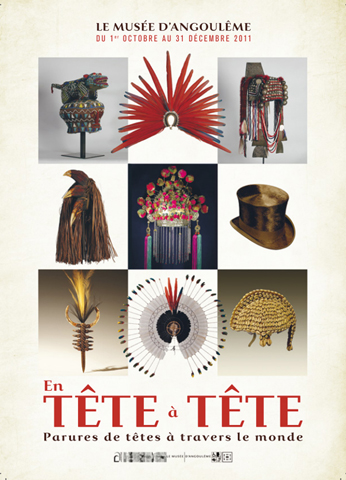

European museums have always collected precious artifacts from ethnic groups whose traditions were destroyed. After any hope of regaining their identifying life-style is gone, an exhibition can celebrate the existence of a culture that can’t threaten what the museum wants to leave out of the narrative. Those who curate, organize, fund, and contribute to it look elegant. Their privilege is living off limits to inquiry.

Princess Lalla Salma, wife of King Mohammed VI, presiding over the opening ceremony of the exhibition.

How many Berbers live untroubled in Morocco?

A minuscule number we are assured.

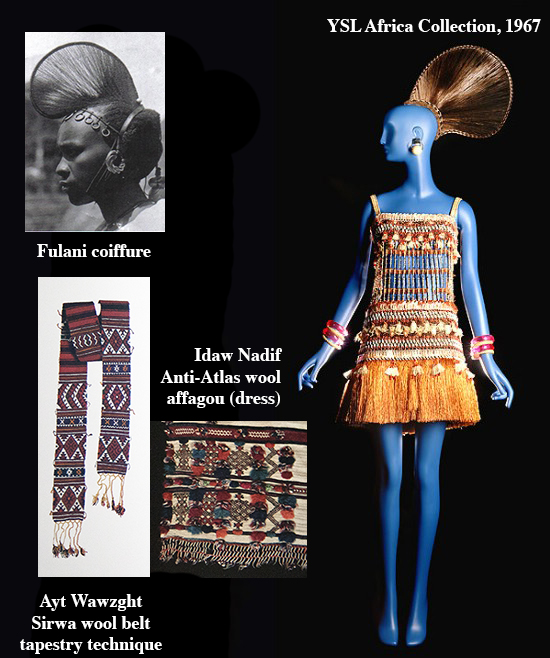

And so an American tourist looks at the beautiful jewelry, falls in love with its exotic nature, remembers Yves St. Laurent’s breathtakingly beautiful, genuinely loving Africa collection (Spring-Summer 1967)…

and goes home to Santa Barbara, California, to entertain a friend.

The coffee tray was delicately set on the table.

“What amazing jewelry. Did you really get to see this in Paris?”

“Yes, Stephen and I had a wonderful second honeymoon.”

“How lovely. Are you going to the Hamptons this summer?”