Mortality comes to us all. My art is the fire that illuminates my home, the warmth that protects me from the freezing waters of a refugee-filled sea — but I’ve seen the videos. Is it morally possible to flutter about one’s curiosities, when the cries of infants go silent as men climb the rope of an Italian cargo ship?

No — but I’ve done it anyway.

I gave many of my combs to the Creative Museum. They were brilliantly photographed, catalogued, kept, respected, and shared because love and family ensconce that world.

Then I will depend on the brainless, computerized repetition of social media — grinding randomly, sharing endlessly. My memories will have long graced the dustbin, as the combs occupy the decentralized, sprinkled intelligence of “I love this!” women on Pinterest.

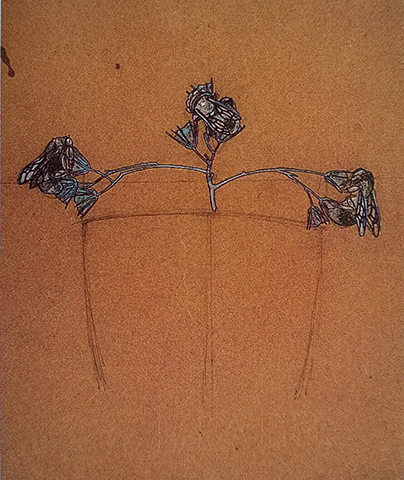

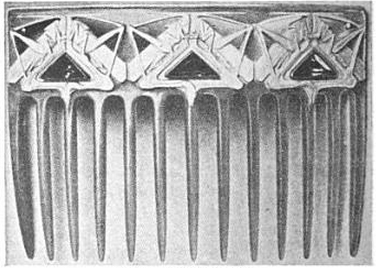

For what it’s worth, this is what I gave the CM. Underneath are their captions:

Superb kushi comb and matching kogai stick made of gold lacquered tortoiseshell. The decoration theme is different on each side. One features a dragonfly in a cobweb; the other shows a small cat playing with a ball. The maki-e work is perfectly made.

Very fashionable late 19th, early 20th c. this kind of ivory comb with traditional Chinese motif was made in China for the Western market. This one is perfectly carved and the phoenix is rounded with bamboos and peonies. Its eye is a tiny black bead.

Handsome decorative ivory comb, carved in China for export in the early 19th century. Background of lace-like punch carvings on which are superimposed roses separated in two parts. Long sharply pointed teeth.

United Kingdom. c. 1870. Very refined ivory comb from the Victorian period. The crown motif is reminiscent of the Peigne Josephine style.

United States. Late 19th Century. Gorgeous comb with a very dynamic and symmetrical shape. It features a phoenix, the Chinese emblem of Empress Cixi.

Japanese set with a kushi comb and its matching kogai stick depicting two drums called Ko-tsuzumi. They are hourglass-shaped drums that are rope-tensioned. Geishas use to play this kind of drum which is a frequent decorative motif on combs.

Late Edo tortoiseshell and lacquer kogai stick. It would have been the smaller stick in a set of three, accompanied by a larger kogai and a comb. The artist created a three dimensional effect in this small rectangular shape. Two plover birds talk to each other as they play in the water.

United Kingdom. c. 1870. Superb comb cut out of one piece of mother-of-pearl that goes to the golden edge of the oyster. It is embellished with pierced and carved spirals.

United Kingdom. Late 19th Century. A mother-of-pearl two-pronged hair pin, pierced with a delicate flying bird against a floral background.

United Kingdom, 19th Century, Ivory. The round heading of this comb is pierced with a peacock spreading its tail. The edge is also decorated to add transparency.

कंघी

For further scholarship, you may examine the publications and exhibitions of the Creative Museum.