Written by Jen Cruse, featuring the collections of Gina Hellweger and The Creative Museum.

Mongol women traditionally wore their thick black hair tied in long plaits falling forward onto their shoulders, placing slightly curved silver combs flat on the top of the head. On festive and celebratory occasions, however, distinctive and colourful costumes were offset by an elaborate headdress constructed over a metal frame and decorated with numerous silver ornaments, temple pendants, combs and hairpins, all richly enhanced by the liberal use of red coral, turquoise and amber sets and coloured enamelling. For the Mongolians, coral symbolized blood, fire and light; turquoise, water, sky and air; amber, the earth.

The two silver hairpins illustrated are decorated with coral beads and coloured enamel. These hairpins were once part of the lavish and complex head ornamentation worn by Mongolian women when dressed in traditional costume; late 19th or early 20th century. Length 4¾ ins/12.1cm.

To my fellow author, and noted collector of tribal arts, Gina Hellweger, thank you for contributing this Mongolian parure. Here we can see how they expressed blood, fire, light, water, air, and sky in all its intense beauty. Gina’s parure is made from silver, decorated with enamel, turquoise, and coral.

She was also kind enough to contribute these two sets of Mongolian hair ornaments, made of the same materials.

Mongolians also symbolized their world with jade, pearls, and black agate. From the vaults of the Creative Museum comes this magnificent, rare barrette. A brass medallion full of pearls surrounds a stone of black agate.

The museum has also contributed this silver hairpin, which is decorated with jade beads and carved flowers. Some traces of the enamel still remain.

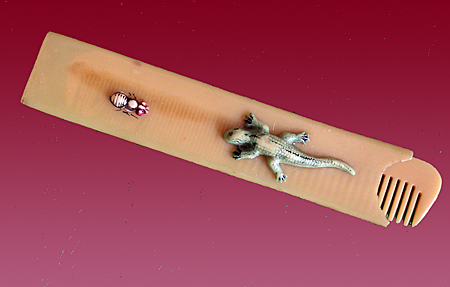

These two silver slide bars are intricately carved with happiness motifs.

It is an honor for me to bring our community together, so we can all be inspired to learn more about the Mongolian decorative arts.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please see the Creative Museum’s exhibition on Chinese and Japanese hair ornaments, as well as these books, which have been added to our Resource Library.

|

Mongol Jewelry: Jewelry Collected by the First and Second Danish Central Asian Expeditions |

The Art of Silver Jewellery: From the Minorities of China |

The Comb: Its History and Development |