When the artist inside rules you, you climb mountains. Society judges you on your idiosyncrasies alone, unless you can communicate why you devoted your life to a love of something. With Kajetan Fiedorowicz, this love was for combs. I believe his artistic eye; his instincts that allow him to understand genius, in whatever condition it comes, from where ever it comes; his taste and class; and his passion for scholarship has made him one of the greatest comb collectors in the world. Hair combs are blessed because he fell in love with them.

He wanted his collection to be a comb museum, but tragedy and unimaginable heartbreak struck. Some scorned him. They tried to beat him. That’s when you know who your friends are. Others never wavered. “Never surrender,” he always said to me.

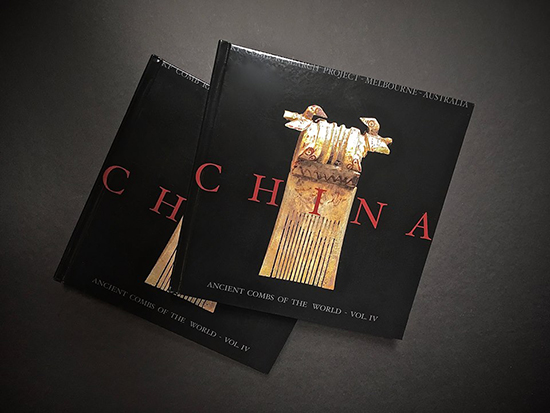

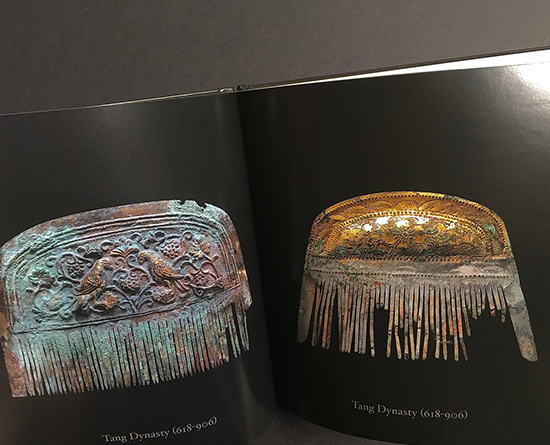

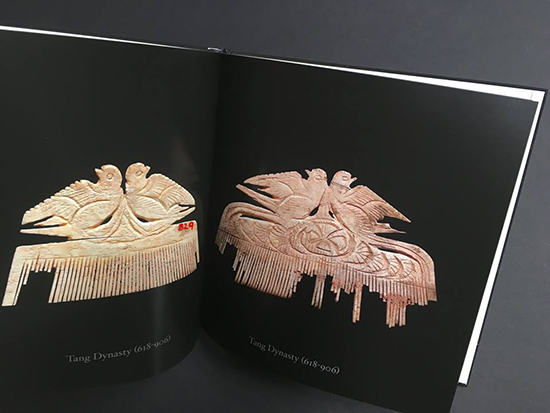

Today that strength of character triumphed. The KF Comb Research Project announced the prototype publication of “China: Ancient Combs of the World, Vol. IV.”

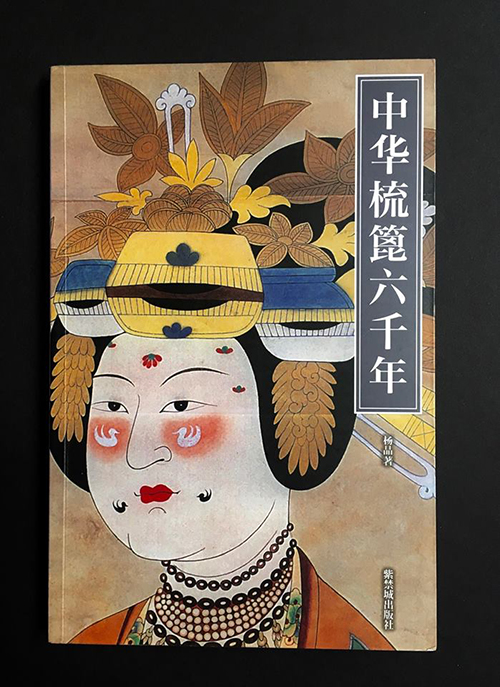

He said, “Very important for this vol. IV on ancient Chinese combs was to get it proof read and checked by someone educated and competent with this particular and very narrowly specialised subject matter. I was fortunate to get through to the best person, Miss Jing Yang, the senior researched in Palace Museum in Beijing,

“who is also an author of the best selling book on a history of Chinese combs and hair ornaments, pictured below.”

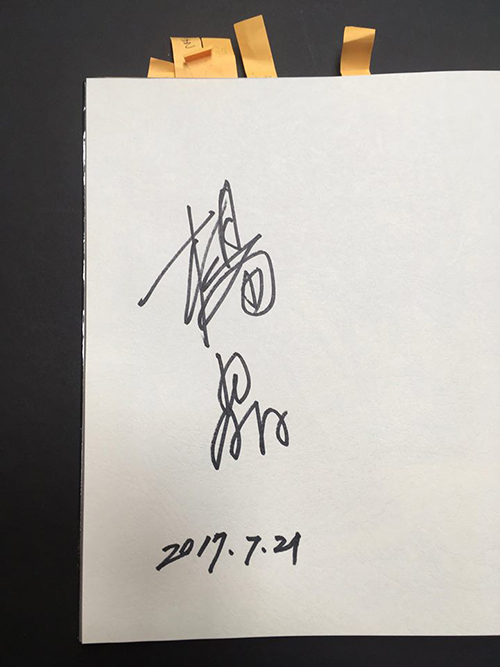

“It has been my honour and a privilege to receive a favourable opinion from such a prominent researcher. And her signature in my book prototype… how epic :) is that.”

“I also thank Wu Yi Shiuan for making this possible.” (Editors note: Wu Yi Shiuan is the founder and head of the Chinese Hairpin Museum)

Kajetan continues, “I’m pleased to report major progress with my books on ancient and ethnic combs of the world. As some of you may know, I’m working on a series of 5 volumes presenting (in pictures) the results of my long time research and collecting efforts, divided by cultural regions. The first test copies were printed and I’m in a process of fixing unavoidable errors.”

Perfect English grammar eludes us all, even those of us who think in English. However, you rarely find an uncompromising purist you can trust to identify every single piece correctly. That takes 30 years to do, and he’s done it. Only love could have produced the photographs in this book.

Kajetan, you changed my life with that Māori comb auction on E-bay. I wrote about you before knowing you existed, and amused you in the process. Then I met you, and you taught me how to see. If you can do this, I can overcome my life’s mountains, too. Thank you for these books. Thank you for your life.