Perched on a silver setting, brilliant plique-a-jour enamel rainbow McCaws brighten up this horn comb. c. 1910, unsigned but numbered.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

Perched on a silver setting, brilliant plique-a-jour enamel rainbow McCaws brighten up this horn comb. c. 1910, unsigned but numbered.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

Ella married painter Charles W.S. Naper, who became well-known for his English countryside landscapes. They lived and worked in Lamorna, a fishing village in West Cornwall. Ella made this pair of lily-pad combs out of green-tinted horn, and created the dewdrops from moonstones, c. 1906.

And here is her portrait, painted by her husband.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

In the Victorian Era, jewelry was convertible. A set of three diamond sprays would come with different fittings. In this 1855 example from Hunt & Roskell of London, the diamond pieces combined to make a tiara or corsage pin, were worn individually as brooches. Or, the two larger pieces could be attached to tortoiseshell side combs. The fittings were placed neatly in the original velvet box, underneath the pad on which the diamonds rested. The initials MP and a Viscount’s coronet were stamped on top. They suggest the diamonds belonged to Mary Portman, wife of the 2nd Viscount Portman, who married in 1855.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

By Jen Cruse:

The fleur-de-lys (often spelt “lis”) motif is frequently encountered on ornamental haircombs, either as part of the overall decorative heading or as an applied embellishment. It is said to represent three central petals of the lily, a flowering plant of the genus iris.

The initial conclusion may be that combs depicting this motif must be of French origin, but not necessarily so. The fleur-de-lys was and still is widely used on innumerable artefacts and textiles around the world, although no doubt it had its origins in France.

Certainly the name is French, meaning the “flower of the lily” or “lily flower” and, according to encyclopaedic references, is a very old pattern that was used as decoration in ancient times in countries as far apart as India, Egypt and Italy.

It first appeared in Europe in the 12th century as a motif on heraldic coats of arms. It was the emblem of the French Kings and was depicted on the French Royal flags, shields and banners up to 1789. When Edward III of England (1312-1377) claimed the throne of France, he added three fleurs-de-lys to the three lions of England, and they remained on the English royal arms until 1800. To this day the fleurs-de-lys are still part of the decoration of the royal crown.

The fleur-de-lys is the adopted emblem of the city of Florence in Italy. It also appears on 17th century tombs in Delft churches in The Netherlands. In religious pictures the motif, like the ordinary lily that signifies purity, is symbolic of the Virgin Mary. The motif also became the emblem, in a modified form, for the Scouting movement worldwide, founded by Lord Baden-Powell in 1907.

The 3 combs illustrating the fleur-de-lys motif are all made from celluloid (cellulose nitrate) and date from around 1910 to 1914.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

The website of the Antique Comb Collectors Club

Janvier Quercia was a French silversmith who worked c. 1900. This hair comb was part of a three-piece silver-gilt parure, which included a belt buckle and necklace. A woman emerging from leaves expressed Art Nouveau’s philosophy of metamorphosis. The buckle was made from a metal die cast from a wax model. A reducing machine altered the size of the die to make the comb. As he was making jewelry, Quercia founded Abdullah, a company that made lighters, which was taken over by his son Marcel in 1948.

Quercia’s hair pin design seems similar to my Elkington and Co. barrette. Elkington invented electroplating silver onto copper in the 1840’s, and my piece was made in England, c. 1900.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

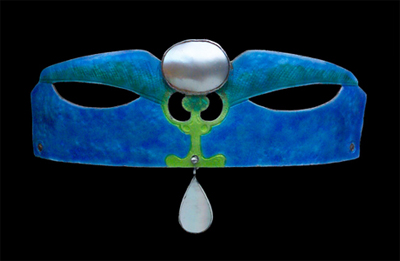

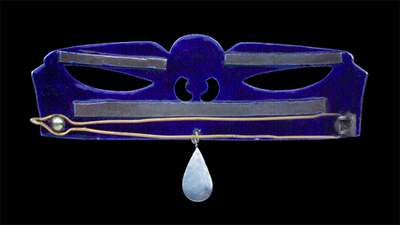

This barrette sports mottled blue and green enamel on a silver backing, with two pearls. Britain, c. 1900. It is in the 1200 to 2500 UKP price range at The Tadema Gallery in London.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

For much of the nineteenth century, tortoiseshell was a luxury material that commanded high prices, whereas horn was a readily available material and inexpensive by comparison. By around 1830, the horn craftsmen found a method of clarifying and staining horn in imitation of tortoiseshell and, over succeeding decades, made combs, hairpins and other small items such as snuff boxes, fans and brooches. Being plausible reproductions of the real shell they, too, achieved similarly high prices and to all but the discerning eye, found a ready market until the advent of celluloid simulations in the 1880s.

The two combs pictured illustrate the remarkable similarities of each material, polished horn and lustrous tortoiseshell.

कंघी

These combs are British, c. 1850-1870, and can be found on page 43 of The Comb: Its History and Development by Jen Cruse

We are a forest goddess with fairy handmaidens who present us with jewelry so we can choose which piece fits our mood. If these two pieces were presented, which would you choose?

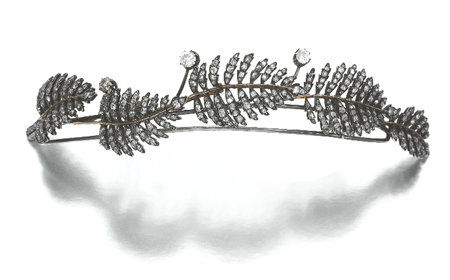

First is a beautiful English diamond tiara made from ferns and circular-cut rose diamonds, c. 1890. It sold for $12,165 at Sotheby’s London on July 13.

Our second piece is a white translucent jade bracelet and comb in perfect condition from the Qing Dynasty (18th Century China). In the bracelet, two dragons confront each other grasping a “flaming pearl.” The S-curved dragon shape was popular in comb making at the time, but this one is made of exquisite jade and is in perfect condition. The pair sold for $7,258 at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2009.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

This beautifully carved tortoiseshell comb is one of only three known to me. Two are in my collection and the third is in the collection of the Museum of London. Each comb varies slightly in format and also condition, and the carving techniques demonstrate the exceptional skill of the combmaker.

The decorative features of each comb originally included engraved emblems of rose, shamrock and thistle (all broken off on this example) together with the Prince of Wales feathers, further embellished with a crown and two fleur-de-lis in rolled gold; European in origin, it is possibly English-made and dates to the mid 1800s.

W 7¼ ins/18.4cm Ht 9 ins/22.9cm

Suggestive of royal connections, for whom these combs were designed or intended is uncertain. Were they to be worn by members of a Royal Court or were they expensive commemorative gifts to celebrate a Royal wedding?

Unfortunately I have been unable to find any precise information on this comb, its ‘sister’ comb featured on page 30 of my book or the Museum comb. Various theories exist but are purely speculative in the absence of reliable evidence.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine

The griffin, or eagle-lion, is generally portrayed with wings, a beak, eagle claws and feathered, and pointy ears. Some traditions say that only female griffins have wings. Griffins found themselves on the cross of St. George, Greek mythology, Persian poetry, Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Divine Comedy.

I saw this comb on Ruby Lane. The dealer mentioned that she didn’t know if it was celluloid or shell. Three seconds after I looked at it, an unconscious force led my fingers to the shopping cart. Suddenly, when I regained consciousness, it had been delivered. I’d say this is a griffin on a hair pin hand carved out of one piece of blonde tortoiseshell, England, c. 1880.