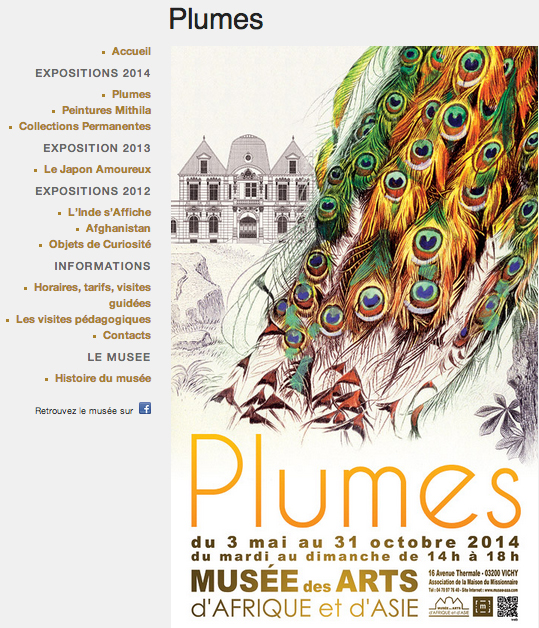

In its second collaboration with the Museum of African and Asian Arts in Vichy, The Creative Museum has been invited to participate in the exhibition, PLUMES.

Human fascination with birds begins when their freedom of flight captures our imaginations. We watch birds soar and glide freely, as their beautiful, feathered wings catch gusts of air. Can we explore birds’ connection to the human soul in other cultures?

The exhibition PLUMES investigates five civilizations: India, China, the Ivory Coast, Papua New Guinea, and North America to show how art reflects human reverence for each culture’s emblematic bird.

Click on the image to go to the exhibition

From India: The peacock is India’s national bird and holds an important place in Hindu epic poetry and mythology. In Rajasthan’s miniature paintings, peacocks provide companionship to wistful nayikas. They are heroines in the Natya Shastra, written by Bharata, c. 100 BC. The Creative Museum’s silver-gilded comb comes from Rajasthan. The well contains perfume, which drips into the user’s hair, and is adorned with two peacocks.

From China: Tian Tsui is the art of cutting and gluing the kingfisher bird’s iridescent blue feathers to gilt silver. The feathers are so small, it is a painstaking task. The term literally means “dotting with kingfishers” and has been a traditional Chinese art for 2000 years. The Creative Museum’s magnificent diadem uses tian tsui. The flowers are topped with three symbolic child figures with painted bone faces.

From the Ivory Coast: The hornbill kaloa bird is the mythological founder of the Senoufo people. One opportunity for young tribal men is to join the Poro Society, a school where most carvings and masks are made. Statues combine human and animal elements. The bird’s horned beak is elongated, as it touches the fertilized, swollen belly. This comb from The Creative Museum shows the beak-belly relationship, as a man wears a kaloa-bird mask, perhaps for an initiation ceremony.

From Papua New Guinea: The Dani People from the Highlands have a fable. Once, a snake and a bird engaged in a great race to decide the fate of human beings. If the snake won, men would shed their skins and live forever. If the bird won, men must die. The bird won. The Creative Museum’s male headdress from the Dani is made of cassowary bone and feathers, crocodile claws, and warthog teeth. It was most likely worn by a warrior.

From North America: The Tlingit are an indigenous tribe who live along the Pacific Northwest coast: now Oregon and Washington in the USA; British Columbia in Canada. Modern-day Tlingit also live in Alaska. Before Christian conversion, they were animists. Their totem poles narrated stories, legends, and myths. The Tlingit have raven clans and eagle/wolf clans. As the eagle’s beak is curved, The Creative Museum’s bone hair pin with a totem pole eye probably belonged to an eagle-clan shaman.

With these five distinct cultural interpretations, The Creative Museum’s contribution to the Plumes exhibit at the Museum of African and Asian Arts in Vichy shows how bird mythology lives on in headdresses around the world.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine our Resource Library and The Creative Museum’s publications and these books:

Kingfisher Blue: Treasures of an Ancient Chinese Art |

Powerful Headdresses: Africa and Asia |

Ethnic Jewellery and Adornment |