One day in 1819, an Indian tiger noticed a party of British hunters. They were obviously lost and thirsty, so the tiger led them to a cave where there was water and went on his way. The Western Ghat mountains near Maharashta can be hard to navigate.

What the hunters found were the painted caves of Ajanta.

Thirty-one of them had been dug into an arc of solid rock. Masterpieces of pre-sectarian Buddhist painting covered the walls. The oldest dated to 200 BC. They told the Jataka stories about the previous lives of the Buddha, from a resolve to give up all worldly goods to “The Turtle Who Couldn’t Stop Talking” to courtship scenes in Indian pleasure gardens.

Mahajanaka renouncing the worldly life, from the Mahajanaka Jataka. 7th century, Ajanta Caves, India

The images were intended for monks, who did not find them inappropriate. Buddha is seen in a courtly environment after his Enlightenment. Love-lorn princesses languish. Courtesans are shown nude but for their jewels. The famous 5th Century playwright Kalidasa wrote, “I recognize your body in liana; your expression in the eyes of a frightened gazelle; the beauty of your face in that of the moon, your tresses in the plumage of peacocks… alas! Timid friend- no one object compares to you.”

Mural of a garden courtship scene

The two-peacock theme spread to many cultures, as Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, and Persian art mixed in India and developed a complementary aesthetic.

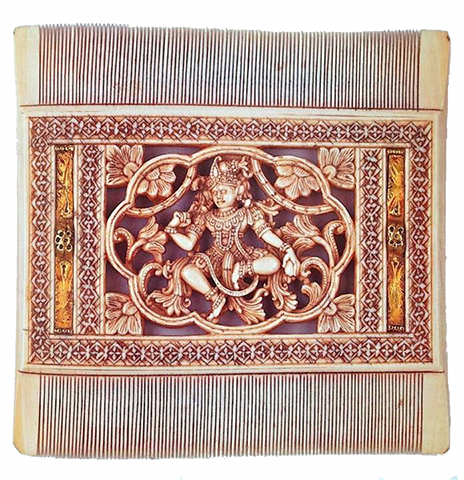

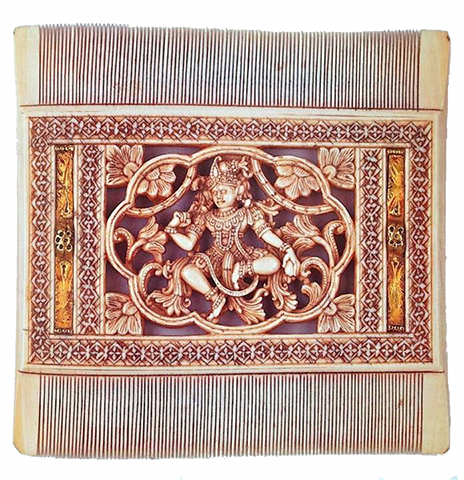

In 185 BC, Pushyamitra Shunga, a Brahman from Magadha founded the Shunga Empire in Northwest India after assassinating the previous Buddhist emperor. Although he is accused of persecuting Buddhists, historians have not been able to prove it conclusively. However, during his reign, Buddhism spread to Kashmir, Gandhara and Bactria. The Creative Museum has an ivory comb from the Shunga Empire (without tines) featuring a goddess.

Also from the Shunga Empire comes this ivory comb from the Cleveland Museum of Art. It is in the style of Chandraketugarh, an archeological site 21 miles from Kolkata in Northwest India. The comb features two goddesses and two peacocks on either side of them, facing each other.

Some of the greatest Hindu combs were carved in 18th Century Karnataka in Southwest India under the leadership of the Nayakas of Keladi after the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565. Religious tolerance was also a hallmark of India’s late medieval period.

Residing in the Museum of Fine Arts Houston is the divine herdsman Krishna and his favorite consort Radha. Some Hindu sects worship the Radha Krishna, as the masculine and feminine aspects of God.

On this ivory comb, Krishna and Rahda tend to four sacred cows beneath their pedestal. He plays the flute and is portrayed as a model lover, while various consorts hold a parasol, fly whisk, fan, and scepter. The bottom section of the comb features five female musicians. On the back is Ganesh, the god of good fortune.

Susan L. Beningson was hired as Assistant Curator of Asian Art at the Brooklyn Museum in 2013. Her collection of Indian Jewelry was featured in an exhibition, “When Gold Blossoms,” which toured the country. She also has ivory masterpieces from 18th Century Karnataka in the last decades of Nayaka rule.

This comb portrays Krishna and Rahda in an amorous embrace, on top of which are two golden peacocks holding a vessel with a ruby knob.

This is another two-peacock ivory comb from Karnataka.

from Kajetan Fiedorowicz

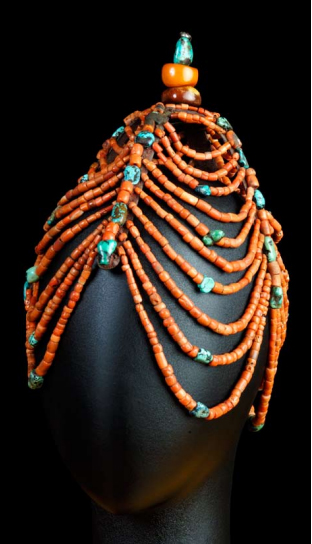

These two combs from the Susan L. Beningson collection come from Madurai, a city south of Karnataka in the state of Tamil Nadu. Ruling from the 16th- to 18th Centuries, the Madurai Nayakas had royal workshops and were credited with massive restructuring work, which spurred economic growth and led to the formation of many new towns. They also developed trade and earned the protection of artisans and merchants.

In this 18th century ivory and gold comb, Krishna is dancing and holding a butterball, two of his most popular portrayals. A scalloped frame surrounds him.

Here, two gold peacocks observe you with ruby eyes, while coral beads hang at the sides.

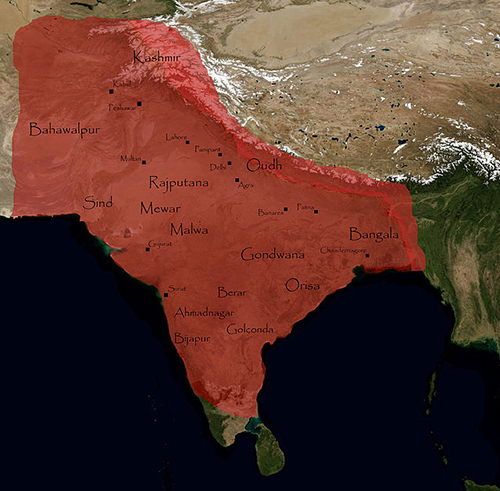

The Mughal Empire in the North of India was Muslim with a Persian ethos. It ruled over Northern India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan from 1526-1857. The Mughals had a centralized government that included members of different religions in their ruling elites. This brought about a cultural mix in art and architecture, containing Muslim, Hindu, Turkic, and Persian cultures, most notably Shah Jehan’s Taj Mahal.

An 18th century two-peacock comb from the North was lighter and more delicate than the combs in Tamil Nadu. This ivory one was sold at Sotheby’s.

This 18th Century silver comb, which is hollow to contain perfume, has two silver knobs and is decorated with the face of a warrior Sultan and his consort.

Kajetan Fiedorowicz

In the first half of the 19th Century, to the West near the Persian border, 18th Century courtly scenes were painted on ivory combs. However, they portrayed sultans, as opposed to Krishna and Rahda.

Kajetan Fiedorowicz

The Creative Museum

In 1805, the British East India Company took power from the Mughal Empire, relegating the Sultans to nominal rulers used for colonial domination. In 1857, the Sepoy Mutiny was repressed, and two years later, the Mughal Empire went out of existence. In 1858, the British East India Company transferred all powers to the Crown.

To pre-Colonial Indians, there was no association of women with sin, no Eve or snake or apple. However, the British, especially Christian missionaries, were horrified at temple walls decorated with “much immodest, heathen-style fornication and other abominations.”

That is when combs started to look like this parcel-gilt silver peacock comb. It was made in Northern India in the early 20th Century. The comb is hollow for the internal well of perfume, and the base has small holes, so the perfume can drip to the teeth and then into the hair.

The Michael Backman Gallery, formerly the Jen Cruse collection

However, artists slip in miracles when no one is looking.

From the Museum of Fine Arts Houston comes this gold comb of lions with ruby eyes from the late 19th to early 20th century.

We are all lucky that art was preserved from societies that practiced religious and cultural tolerance, for then artists were free to combine diverse elements and create extraordinary pieces. Once government becomes intolerant and blind, like the British who wanted to make all the world England, imagination shuts down. People just find an acceptable design and make copies.

Postscript: I would like to thank Kajetan Fiedorowicz, without whom I could not have written this piece.

Times Books International, Singapore. 1994 [p.72]

Cole, W.Owen. and Sambhi, Piara Singh. Curzon Press, Richmond, Surrey. 1990/1997 [p.90]

![2016 - Sikh Khanga combs in wood [for BS] 2](http://barbaraanneshaircombblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-Sikh-Khanga-combs-in-wood-for-BS-2-300x225.jpg)

![2016 - Sikh Khanga combs in wood [for BS] 1](http://barbaraanneshaircombblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-Sikh-Khanga-combs-in-wood-for-BS-1-300x225.jpg)

![2016 - Sikh Khanga combs in ivory [for BS]](http://barbaraanneshaircombblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-Sikh-Khanga-combs-in-ivory-for-BS-300x225.jpg)