An important comb type, little publicised and infrequently encountered, is a notable feature of the orthodox Sikh community whose peoples, now dispersed throughout the world, originated mainly from the Punjab State of north-west India, bordering on Pakistan. This is a territory through which the 5 tributaries of the river Indus flow – the word Punjab signifies “the land of the 5 rivers”. Amritsar is the state capital, their language is Punjabi.

The term Sikh is derived from the Sanskrit word Shiksh meaning “to learn”; in Punjabi, it is translated as Disciple.[1] A Sikh initiated into the Khalsa is regarded as an “orthodox” Sikh, belonging to the community of Amritdhari. Founded by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699, he gave Khalsa Sikhs five distinguishing marks of identity, the five sacred K’s or Panj Kakke, and a code of conduct setting them apart from other groups and requiring them to live pure lives.[2]

According to a post on Beard Gains, men are barred from cutting any body hair or beard – Kesh – and expected to wear a turban; to wear a Kachh, a pair of shorts (underpants), as part of the required clothing; a Kara, a bangle of steel or iron, to be worn on the right wrist and a Kirpan – a short dagger, a sword with curved blade, or a knife of similar shape – always to be carried on the body; a Khanga (Kanga) comb worn in the hair under the turban to hold the topknot of the Kesh in place, symbolising personal hygiene and cleanliness in body and spirit.

Before putting on his turban, the Sikh plaits his hair into one long braid, winding it up and securing it on the top of the head. Into this the comb is inserted for safe keeping. Women are expected to observe a similar but modified code and may have a Khanga attached with a black cord tucked under a bun. The tradition is, however, tending to die out in recent generations.

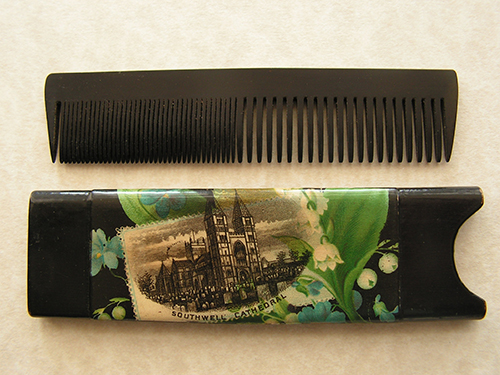

A Khanga comb is a small grooming tool having a distinctive shape with the ‘shoulders’ usually sloping sharply downwards from a rounded or squared top edge. The small teeth are fine cut or sawn, mostly by hand. In many cases, the guard teeth are angled outward at the lower tip. These combs were made in wood, ivory and rhino tusk or in buffalo horn but not cattle horn.

The combs measure between 1 ½ -2 ¾ ins (4-7 cm) in width and 1 ¼ -1 ¾ ins (3.5-4.3 cm) in depth. The illustrated combs are all dating to the later 20th C although the 3 small ivory examples are much earlier.

References:

1. Srinivasan, Radhika. Cultures of the World: India. Times Books International, Singapore. 1994 [p.72]

2. A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism: Sikh Religion and Philosophy (Popular Dictionaries of Religion) 1 New edition by Cole, W. Owen, Sambhi, Piara Singh (1997) Paperback Cole, W.Owen. and Sambhi, Piara Singh. Curzon Press, Richmond, Surrey. 1990/1997 [p.90]

Jen Cruse is author of the authoritative reference The Comb: Its History and Development

![2016 - Sikh Khanga combs in wood [for BS] 2](http://barbaraanneshaircombblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-Sikh-Khanga-combs-in-wood-for-BS-2-300x225.jpg)

![2016 - Sikh Khanga combs in wood [for BS] 1](http://barbaraanneshaircombblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-Sikh-Khanga-combs-in-wood-for-BS-1-300x225.jpg)

![2016 - Sikh Khanga combs in ivory [for BS]](http://barbaraanneshaircombblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-Sikh-Khanga-combs-in-ivory-for-BS-300x225.jpg)