Are many beautiful things for sale, each with their own story, that condense post into one subject is difficult. So I have buffet of things today. Just click the picture or link see more details about each item.

In Sotheby’s Unsold category:

On 6 December 2002, this Henri Vever gold, enamel, and horn hair comb was estimated at $8,000 to $12,000, but did not sell.

On 13 June 2000, this French gold, enamel, and diamond Eugenie comb, c. 1870, was estimated between 6,000 to 8,000 GBP, but also did not sell.

Sotheby’s Upcoming Auction:

Up for auction on 14 November 2014 is brass Alexander Calder hair pin, c. 1940 (Calder Foundation Archive number: A16974). Estimate $50,000 – $70,000. To me, this comb looks like a female body wired into a frame. The estimate is consistent with the Calder market, and the interested to know what it fetches.

Will it appreciate in value, as did Calder’s silver “Figa” hair comb?

“Figa” in Slavic and Turkish cultures is hand gesture made to represent male or female sexual organs. The first and second fingers wrap the thumb. It could in response to money request or plea for physical labor. In Ancient Rome, the gesture was ward off evil spirits.

Calder gifted it artist Frances J. Whitney, c. 1948 (Calder Foundation Archive number: A22629). It could just see her wearing it with a geometrically cut black dress to charity ball, with no one else knowing what it meant but her.

On 15 November 2006, it purchased from Whitney estate for $57,000. On 14 November 2013, that buyer sold for 137,000.

That Live Auctioneers, another comb caught my attention. It is Russian, c. 1908-1917, silver, and made Fabergé work master Anders Michelson (marked AM). The comb has eight tortoiseshell prongs and a beautiful hinge that fits over to entire top. Michelson used niello, black mixture of copper, silver, and lead sulphides, to inlay the dogs and floral pattern on tiara. The auction starts on 13 November 2014, and the opening bid is €300.

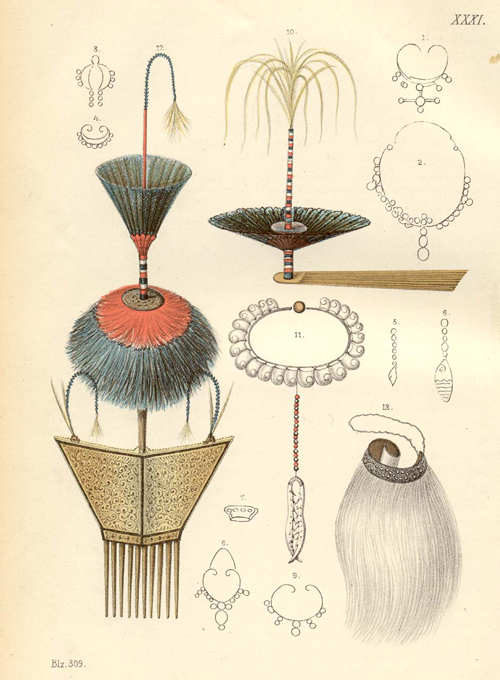

Michael Backman Gallery

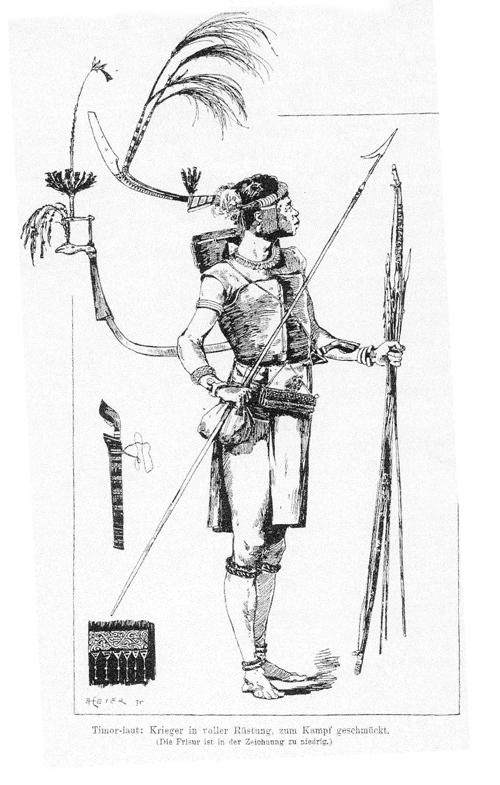

Michael Backman Ltd. this selling pair of gold and at gilded silver-filigree dragon hair pins from China’s Qianlong Period (1735-1796). They have dragon heads, each, which have turquoise cabochon. Openwork hair ornaments were known as “tongzan” and were worn from Ming Dynasty onwards.

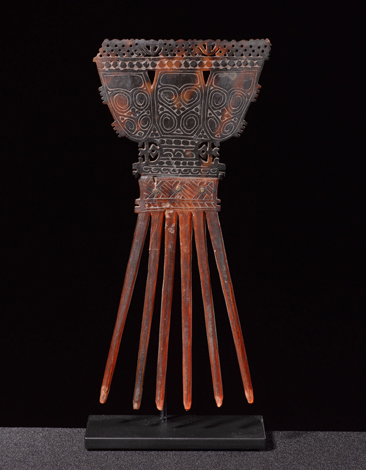

Also on sale this comb from Solomon Islands. It is faa, or man’s woven comb from the Kwaio People, Malaita, Solomon Islands. Woven from yellow-orchid and coconut-palm-frond fibres, the comb was dyed with that geru root. Its teeth are made of fern wood.

The last lot to feature from Michael Backman is jaw-dropping collection of 38 Indonesian gold ornaments, c. 800 AD. It is largest set of gold regalia ever collected for statue in Central Java, Indonesia. Their script on chest cord translates as “‘The weight of pailut with the diadem: 2 suvarṇa, 1 māṣa, 2 kupaṅ’”

Some Lovely Things on E-Bay

Never dismiss E-Bay. A Māori Paikea comb with ivory patina to-die-for was listed by God-Save-Whom for $9.95 with no reserve. The description was “Possibly African.”

It is There are 6 bids on it, including 2 experienced bidders. It’s real tortoiseshell. As printing, are 3 days and 11 hours this auction.

It is Their seller thinks French. It could French or Edwardian English because jewelers in both countries made these types of pins. The auction has 4 days to go.

Of authors, Miriam Slater, as selling this It is rare, it is real, and I’d get my hands on it if I could.

Choosing one amongst many beautiful things is difficult. Mustn’t we just have them all.

कंघी

To have fun researching more items like these please consult our Resource Library and these books:

Gold Jewellery of the Indonesian Archipelago |

Calder Jewelry |

Ethnic Jewellery and Adornment |