The setting of gems is profound meditation. How can a tiara or crown give its wearer the verisimilitude of God on Earth? Rene Lalique couldn’t care less. He transformed the appearance of jewelry with new themes.

Combining French Symbolist philosophy with ideas from Japanese art, he incorporated gem setting into raptors’ claws in this comb, made of horn, enamel, and sapphires. It sold for 92,500 euros on 6/14/2013 at Brissonneau Auction House, Paris;

rain, in the moonstone drops falling from blonde tortoiseshell buds in his famous Moonstone Tiara;

and tree-branch garlands. This tiara has leaves of green enamel with small diamond flowers, which are decorated with a mabe pearl garland. It sold at Christie’s for $112,561 on 6/17/2008.

However, being a keen ethologist, two of his pieces stand out as exemplary expressions of animal behavior.

“Head with Rooster Headdress” resides at the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian. It is made from silver, enamel, and alabaster, and minutely details the intricacy of rooster feathers. What makes this piece special to me is the ruby set in the rooster’s mouth. In real life, roosters eat red currants.

In Lalique’s dragonfly tiara, his golden insects have plique-a-jour enamel wings, but they are also behaving. When dragonflies fly at night, migrating or not, they fly toward the light. Lalique symbolized a light in the dark with an aquamarine.

Art Nouveau jewelry was not only art, engineering, Japonisme, and Symbolism. The gems set in tiaras, diadems, and combs went from symbolizing a wearer’s godlike status to accurately representing a rooster’s breakfast.

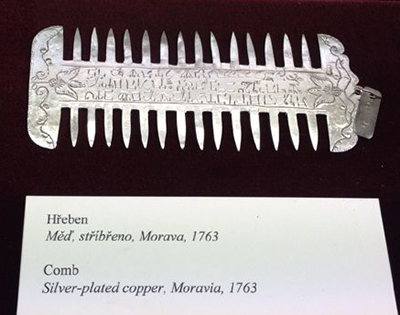

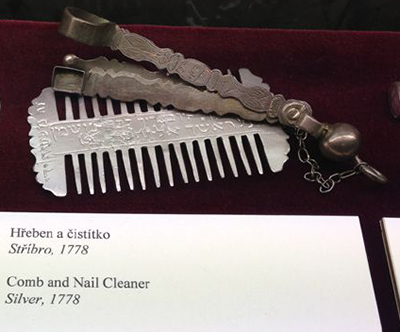

कंघी

For more scholarly research please examine our Resource Library and these books:

The Jewels of Lalique |

Rene Lalique at the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum |

Rene Lalique: Exceptional Jewellery, 1890-1912 |