Early rabbinical texts disclaim the Hellenistic notion that a crown, or keter endowed its wearer with divine and immortal life. Instead, the keter became a symbol for 3 covenants with God: keter malkhut, crown of kingship, given to David for conquering the Ammonite capital of Rabbah; keter kenunah, the priesthood, given to the descendants of Moses’ brother Aaron; and keter torah, the revelation to Moses at Mount Sinai, the crown of God.

Keter Torah, Assayag Synagogue by David R. Crowles (Tangier, Morocco 2002)

The keter torah and the Ten Commandments tablets may also be accompanied by two lions, symbolizing Moses and Aaron, as in this closeup of a crown from Odessa.

In Eastern Europe’s Galicia, this keter’s inscription refers to Deuteronomy 32:11, “As an eagle stirs up her nest, broods over her young…” The animals on the crown’s base represent those that would be sacrificed at the Temple. This silver folk-art crown was made during the 18th- to 19th Centuries and is part of the Michael Steinhardt Judaica Collection. I find it especially interesting because the double-headed eagle with a crown in the middle is also the Russian coat of arms.

These flat finials come from Afghanistan, 1978, and are one of three sets to go on top the Afghani Torah case. The custom of calling finials keter torah is also practiced in Eastern Persia, where most Afghan Jews came from. The ornaments reside in the Center for Jewish Art in Jerusalem.

In the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, a wooden box with two sets of finials on top, called a tik is preserved from a Sephardic synagogue during the Ottoman Empire, c. 1860.

On April 29, 2013, Sotheby’s auctioned this Venitian torah crown with two finials, c. 1730. From the Michael Steinhardt collection, it sold for $437,000. I am sure you can imagine how such a heavy crown with bells ringing on top of the torah case added drama to the service.

In 17th Century Poland and Ukraine, mysticism expressed in kabbalah founded different forms of Hasidic Judaism. The tree of life, or sephirot, comes from kabbalah. So does devekut, a mystical trance-state where one clings to God. Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810) combined kabbalah and torah scholarship, making the mind the central route to the heart. At the top of the sephirot is the keter. It symbolizes the most hidden of all hidden things, incomprehensible to man.

This torah crown comes from Poland, c. 1840. It was sold by Skinner’s for $65,174.

And in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, Hasidic Judaism is vibrantly alive.

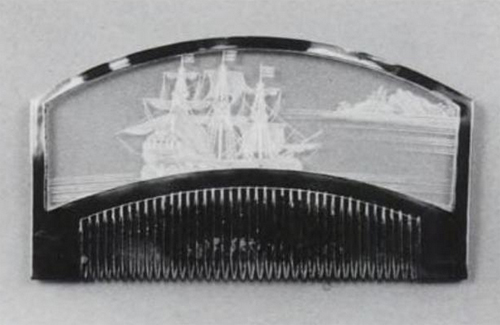

מסרק

For more scholarly research, please examine