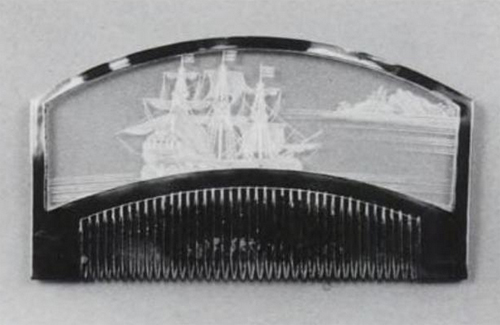

In my book Ethnic Jewellery and Adornment (Ethnic Art Press and Macmillan, 2009), I described and illustrated (p. 170) a very rare comb from Tanimbar, situated in the east of Indonesia, in the southern Moluccas (Maluku). I was unable to show there the only drawing of a person actually wearing the comb, which together with another drawing and further material was found for me by a very helpful Dutch librarian of the World Museum in Rotterdam, who examined a number of rare and old books for the purpose.

(Ethnic Art Press and Macmillan, 2009), I described and illustrated (p. 170) a very rare comb from Tanimbar, situated in the east of Indonesia, in the southern Moluccas (Maluku). I was unable to show there the only drawing of a person actually wearing the comb, which together with another drawing and further material was found for me by a very helpful Dutch librarian of the World Museum in Rotterdam, who examined a number of rare and old books for the purpose.

One aim of this article is now to publish the two drawings mentioned, together with some information contained in the text of these books.

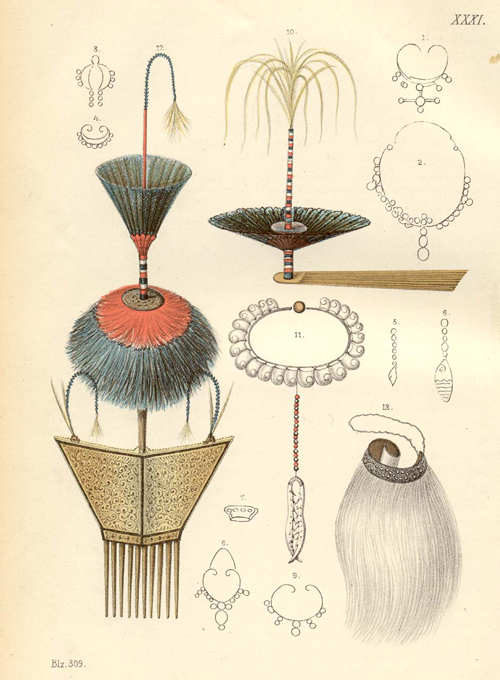

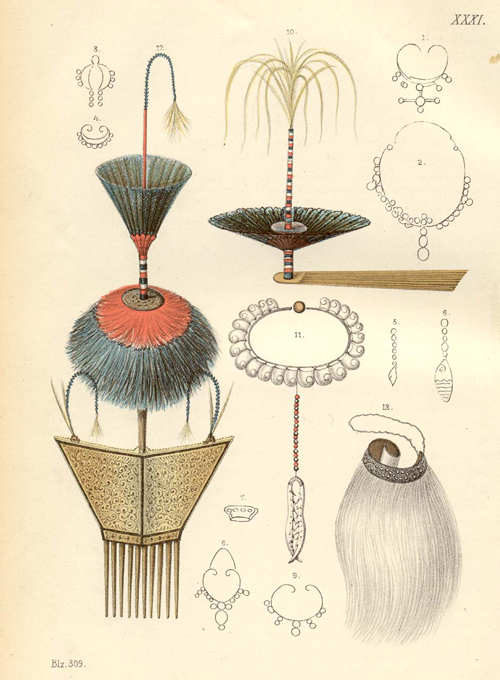

Not many good and genuine examples of this type of comb seem to exist. Perhaps they were always rare, for they were only to be worn by ‘heroes’ (waduwan) according to a description in a Dutch book by J.G.F. Riedel, published in 1886 by Nijhoff in The Hague, De sluik- en kroesharige rassen tusschen Selebes en Papua , of which the title translates as “The Straight- and Curly-haired Races between Celebes and Papua.” The illustration on page 309 of Riedel’s book (shown below, and also reproduced in Suzanne Greub’s Expressions of Belief, 1988) provides a drawing of several gold ornaments from the region, a bamboo comb worn by young men (number 10), and an example of our type of comb (number 12), here called suar taran wulu. It shows some of the ornamentation that was in this case attached to the comb. The comb was worn together with a neck ornament (number 11) called wangap. Number 13 shows a goats’ hair ornament also worn by the waduwan, tied around the leg below the knee.

, of which the title translates as “The Straight- and Curly-haired Races between Celebes and Papua.” The illustration on page 309 of Riedel’s book (shown below, and also reproduced in Suzanne Greub’s Expressions of Belief, 1988) provides a drawing of several gold ornaments from the region, a bamboo comb worn by young men (number 10), and an example of our type of comb (number 12), here called suar taran wulu. It shows some of the ornamentation that was in this case attached to the comb. The comb was worn together with a neck ornament (number 11) called wangap. Number 13 shows a goats’ hair ornament also worn by the waduwan, tied around the leg below the knee.

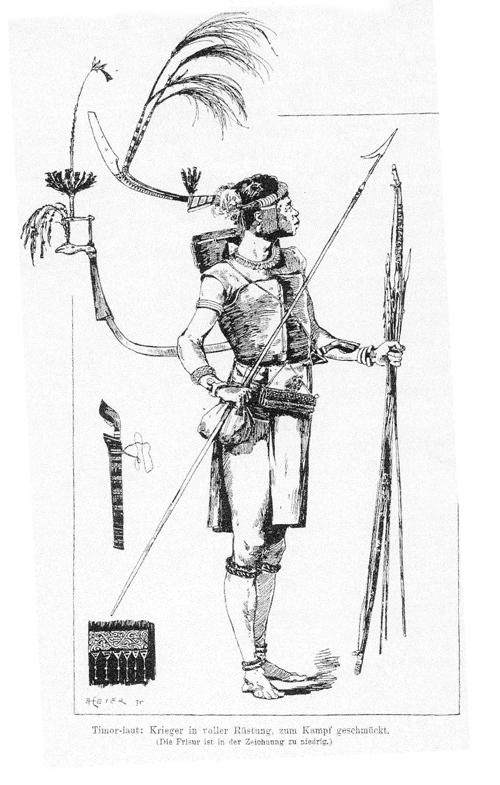

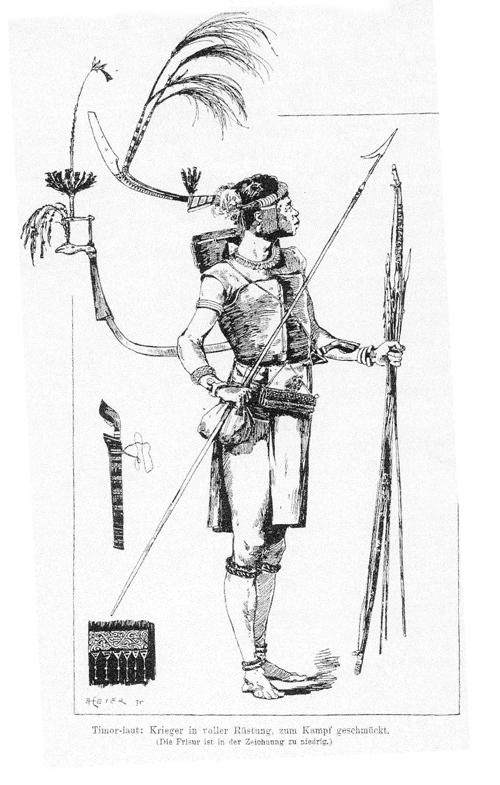

The other illustration found, of an actual wearer of the comb in full regalia, and shown below, was discovered in a German book published in Berlin in 1896 by A. Jacobsen, “Reise in die Inselwelt des Banda-Meeres,” which can be translated as “Travel in the Island World of the Banda Sea.”

which can be translated as “Travel in the Island World of the Banda Sea.”

This shows a warrior decked out for fighting. The tines of the comb were inserted horizontally into the hair at the back. The volume of the wearer’s hair was enlarged by artificial padding and by adding more actual human hair. The warrior’s hair may also have been strengthened by chalk (Riedel, p. 292). The comb was then augmented with further embellishment by the use of a prow-shaped insertion of light wood decorated with feathers or flags. Text under the drawing explains that the hair-do as shown in the drawing is ‘too low’.

Jacobsen had personally watched a dance during which the comb was worn. The drawing describes the warrior as a resident of ‘Timor-laut’. Rita Wassing-Visser, from the Nusantara Museum in Delft, states in Sieraden en Lichaamsversiering uit Indonesië (1984) that the comb is called suar sair or flag comb (p. 129), while Suzanne Greub, in Expressions of Belief , featuring masterpieces in the Rotterdam Museum, gives the name yole to a similar comb collected in the Babar Islands, which lie between Timor and the Moluccas (p. 234). Greub reproduces the illustration from Riedel, but appears to be unaware of the drawing from the book by Jacobsen.

, featuring masterpieces in the Rotterdam Museum, gives the name yole to a similar comb collected in the Babar Islands, which lie between Timor and the Moluccas (p. 234). Greub reproduces the illustration from Riedel, but appears to be unaware of the drawing from the book by Jacobsen.

Obviously the comb was used in a number of island groups, under different names and with different kinds of decoration. Wassing-Visser calls the accompanying necklace of large cowrie shells wangpar, and states that a second necklace often worn with the comb, indar-lele, was usually made from swordfish vertebrae or sawn buffalo bones.

Jacobsen (p. 217) explains that the carved inlay on the comb consists of ivory, and this is stated about a number of examples. The Moluccas certainly imported ivory and attached great value to it, but our example and several others in illustrations appear to have used bone for the inlaid and carved sections.

Not a single photograph seems to exist showing the comb as worn. Several similar combs in the collections of the World Museum are described as having been damaged or gnawed by rodents, consistent with the combs having come from graves. This suggests that in many cases they may have been buried with their owner.

Our example was collected by Dutch people in the 1970s, in the village of Alusikarwain in Tanimbar Selatan, or South Tanimbar, and clearly dates from the nineteenth century. It was said to have been used in dance ceremonies called Tabar Lla or Ngabar Lla. It is a pity that the nineteenth century travellers either had no camera or that their photographed material did not survive tropical conditions, and apparently later visitors no longer saw the combs used in dances.

कंघी

Sources:

Greub, Suzanne (ed.) 1988. Expressions of Belief: Masterpieces of African, Oceanic and Indonesian Art from the Museum voor Volkenkunde , Rotterdam. New York: Rizzoli International.

, Rotterdam. New York: Rizzoli International.

Jacobsen, A. 1896. Reise in die Inselwelt des Banda-Meeres . Berlin.

. Berlin.

Riedel, J.G.F. 1886. De sluik- en kroesharige rassen tusschen Selebes en Papua . The Hague: Nijhoff.

. The Hague: Nijhoff.

Wassing-Visser, Rita. 1984. Sieraden en Lichaamsversiering uit Indonesië. Delft: Volkenkundig Museum Nusantara.

कंघी

Please read an interview with Truus Daalder on the blog, Pierre Nachbaur Art. Ms. Daalder is the author of