BarbaraAnne, “National boundaries change. What happens when you are left behind? What happens when your people have inhabited a land for 9000 years, and others who conquered it less than 200 years ago call them foreigners? As a native son, how do you become an artist, make beauty out of alienation, and find your identity?

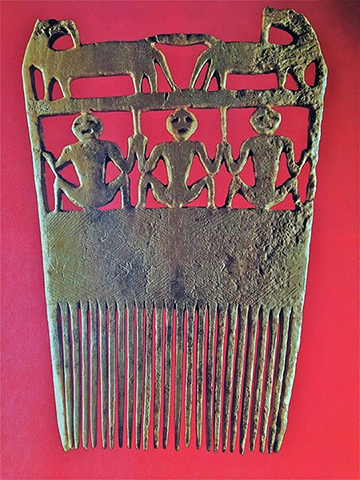

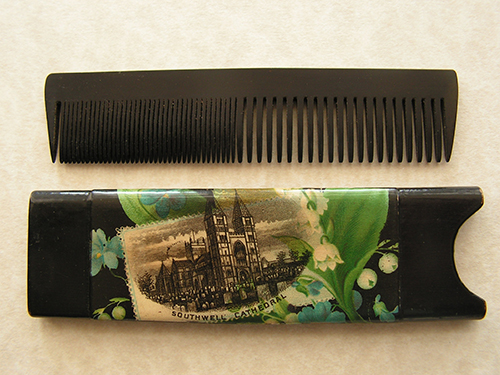

One Pomo Indian / Mexican Indian man made this comb:

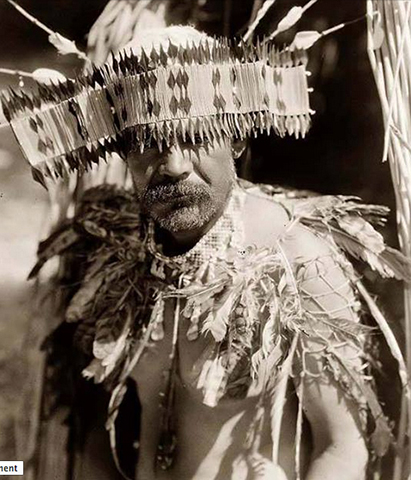

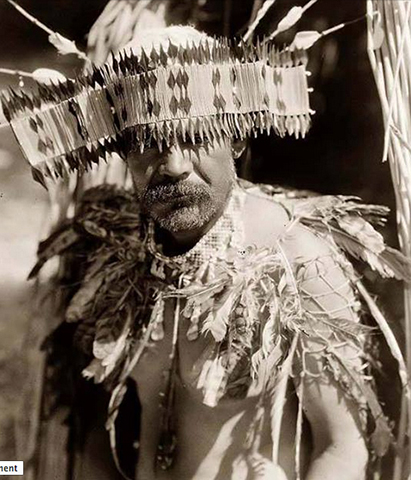

after living through this:”

—————-

Coming “Out” as a Native American (And possibly “Mexican-American”) artist: by Carving Cat

For the early part of my life, “race” defined quite a lot of the boundaries of my world. When you grow up poor AND brown, for some people in the US, that’s a double sin. In their minds (perhaps), it’s not enough that you are a “Foreigner”, but that you would additionally have the audacity to also be one of the poor, huddled masses.

I had been told many times, even as a child, to “Go back to where you came from” and “You people ruin this country.” Except where I “Came From” is California. Where my mother comes from is California. And so on, back 9,000 years.

And on my father”s side? Michigan. And my father’s father? Texas. His father? Texas. And my great grandfather? Texas. And before that, the area where they are from (El Paso, Texas) was part of Mexico.

My mother (Being full Native Pomo) had always told me that “We” were the “Real Americans,” and that everyone ELSE should “go back to where THEY came from.”

Which sounded (As a child especially) even worse to me, since I had known what it felt like to not be wanted, even by people whose parents had come to the US, perhaps even just 70 years ago…

On my father’s side, they were as American as flower tortillas, which is in fact VERY American these days, considering that one can purchase some kind of “wrap” anywhere.

My father’s people had lived as farmers in what was then a province of Mexico. Not as land owners, but as “dig in the hard dirt with your bare hands” farmers. My grandfather was quite Spanish-looking. My grandmother was a small, compact woman who was very much the “Mexican Indian.” She was as dark as polished wood, with strong, sinewy muscles. She had held her large family together through war, alcoholism, gambling, and racism.

My father was born in the 1940s in Michigan, where his parents were living (Working) at the time. It’s quite possible that my grandfather was working in one of the steel foundries there, since his next move involved going to California to work in another steel foundry.

In terms of character, it’s quite hard to place my father. As I remember him, he was strong, smart, grumpy and extremely kind (He could usually keep his grumpiness to himself…), very close to nature.

He had grown up in an age of the “great melting pot”, where “immigrants” were expected to drop their culture and language, in preference of creating a unified, “American” culture. My father had grown up speaking Spanish in the home and outside of the home. It was forbidden (I believe) to speak it by my grand parents.

My father was the epitome of the “God-fearing American.” He honestly believed that America was the greatest nation in the history of the world, where fair play and family values took precedence over anything else. A place where all men were equal (Yes, men…), people worked hard, and to be anything else was patently un-American. He had very much of a love-it-or-leave-it attitude.

Tragically, his ideals failed to work out for him because he didn’t “look” American, even though he wasn’t an immigrant, nor the child of immigrants. America moved over HIS ancestors.

What does an American look like? In all of my travels over more than a decade, the answer is “White” or possibly “Black.”

My father grew up in an era where people would routinely be persecuted for the simple fact of being the “wrong” color, in the “wrong” place. I now suspect that the root of my father’s American Nationalism came from his early treatment by people who regarded him as a “foreigner”, purely on the basis of his skin color. It could even be possible that he faced “racism” at the hands of Mexican-born Latinos, for not being a “real” Mexican, as I had later on.

I believe this treatment engendered in him, his later anti-Immigrant sentiment. I can only suspect this, for I never got the chance to talk about this subject with my father before he died.

He believed that everyone in the US should speak only English, that people needed to melt in or go back, and he was especially hostile to illegal Mexican immigrants even though he spoke perfect Spanish himself. At the start of the Vietnam war, my father was quick to join the Air Force and be sent off to Vietnam, something that haunted him for the rest of his life.

My mother was born in California, to a Pomo mother, and I suspect a Pomo father. Very early on, she had been adopted. For the next 25 years, she would know that she was “different” (Being Native-looking) but not knowing her tribe, her past.

She told me that she had been adopted by a very kind Italian-American man and his a not-so-kind wife.

After her turbulent childhood, she had managed to track her mother down and learn about her Pomo ancestry, some of her background before being put into adoption and so on. Sadly, this never turned into a proper relationship because of my biological grandmother’s mental illness and hostility towards my mother.

Growing up with such a difficult past and perhaps even facing discrimination for her appearance (Big, “Indian” and “mean looking” would be a proper description I believe, much to the pleasure of my mother…), she naturally gravitated toward other Natives and sadly fell into the crowd where alcohol and drug use were commonplace. It’s a long subject, but take it on my word that Natives lack the ability to process alcohol properly, leading them to alcoholism more easily than other groups.

My mother had always taught me that “We” were the “real” Americans and even from an early age, it left a bad taste in my mouth. We spent much time (Whenever we were living in Oakland California) at the Intertribal Friendship House, a community center that helps to organize events for Native Americans in the Bay Area and helps to address social and medical issues that especially plague the Native population, such as alcoholism, abuse, homelessness and drug use.

Skipping ahead…

As a teenager, I had been turned off of “Choosing sides” by the rampant racism and nationalism and just pure stupidity I had seen, both within my family and outside.

I just wanted to be me: an artist, a person and someone who loved the natural world. Could I be called a “Native American or Pomo” artist? Had my tenuous connections to my tribe affected my art? Was my handcrafting genetic?

I had seen some of the amazing Pomo baskets and artifacts at the Oakland Museum and knew that probably, one of my relatives had made them, somewhere near Clear Lake or Santa Rosa, California.

Even at a young age, I had known. Did their patterns influence my art?

As a “Latino” or “Mexican American”, was I influenced by the ever-present Mexican culture in the Western States?

I didn”t even speak Spanish and wasn”t a “Real” Mexican, according to some classmates who WERE culturally “Mexican American.” At that point, I had resolved to drop these “racial” and “cultural” connections, to just be an “Artist”, without these kinds of add-ons.

It wasn’t shame that had led me to that point, but pure exasperation. I had been treated like a foreigner all of my life at that point so I didn’t much care about the “American” label. I also hadn’t been particularly involved with the “Mexican” part of my genetic heritage. The only culture I HAD been welcome into was the “Native” culture.

At various points I had been involved with social organizations of Natives, including the “Native American Youth Council,” through the Intertribal Friendship House.

No, I’ve never lived with other Pomos, crafted with them or learned “our” traditional ways. Am I a “Native American” artist? Or “Mexican American” artist? Or even an “American” artist?

It’s not for me to say. I will leave it to others. For now, I will just make art and be an “artist.”

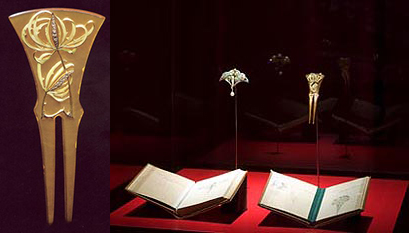

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine