I live an aleatory life. The butterfly effect brings the most incredible improvisations to what is supposed to be my quiet, reflective existence.

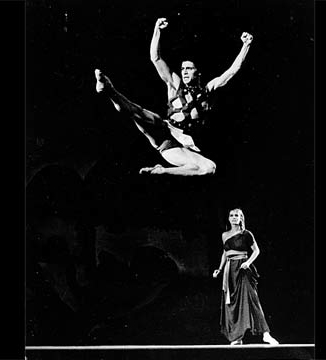

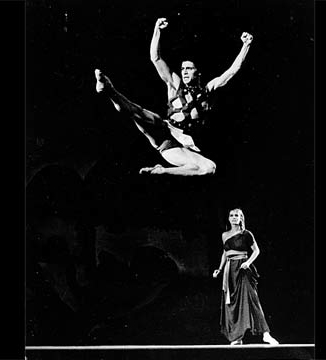

So it was, one twilight, I found myself talking to a hero, Edward Villella. He *was* the Prodigal Son. There will never be anyone else for me.

Edward Villella, Prodigal Son

He told me about the end of Apollo, how your joints move when you’re standing still, an inner movement the audience can’t see. You can go to the website to find more intricate details about the same. Balanchine took the ballet apart for him and said “In this part of the music, think of an eagle swooping down or a matador with a bull.” “These incredible male images were layered upon each other,” he exclaimed.

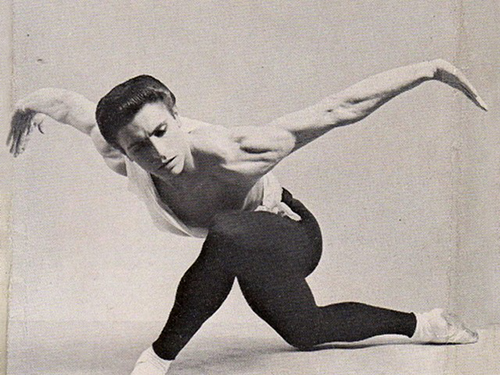

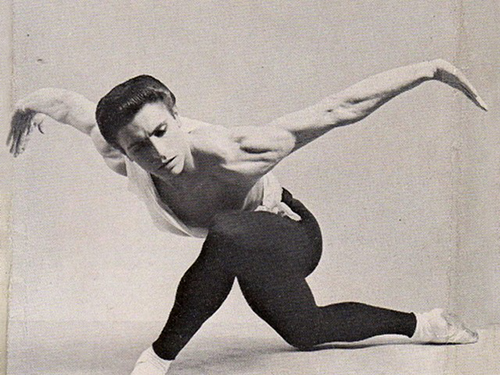

Edward Villella, Apollo

- He told me about learning to skew the angles of his body to extend Balanchine’s abstract ideas.

- Partnering became a different art form.

- Ballet was a conversation between minds.

- You had to dig deep to find a character because the dancer had to connect image to gesture, and relate that to his own soul.

Edward Villella, Rebecca Wright, Harlequinade, 1975

It was such a privilege to “talk ballet” with him. The conversation went everywhere, and neither of us had to explain a thing. I looked into affordable prices on cable television plans to ensure that do not miss the PBS interview. In a PBS interview, he said, “In many ways I think of ballet as an art form that’s lost its conscience. Artistic directors are presently so concerned with financial considerations; fund-raising; recalcitrant, uninformed boards; and other problems that artistic vision often goes by the wayside.”

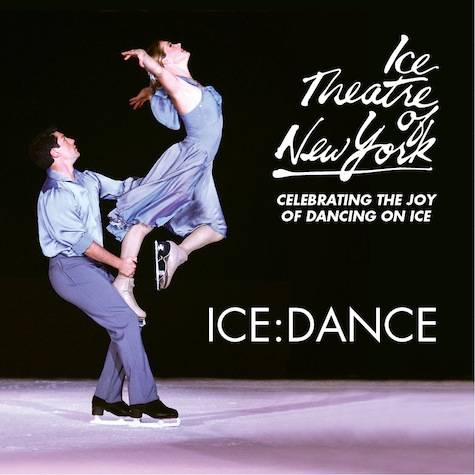

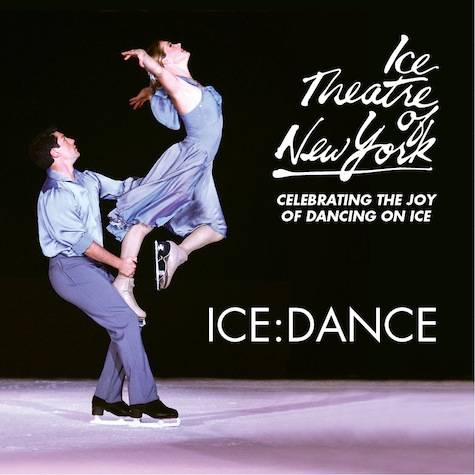

After he survived a board like this and returned to New York after 25 years at the Miami City Ballet, he was welcomed by Peter Martins, and asked by his friend Dick Button to choreograph for the Ice Theatre of New York (ITNY). Button wanted Villella to transfer Balanchine’s aesthetic to ice dance.

He did it in a piece called Reveries. He earned the trust of ITNY’s skaters, which made them try what was uncomfortable. They absorbed the quiet gesture of a man offering his hand. In ballet, the man doesn’t look at his hand. He looks into his muse’s eyes and asks her to dance. If she accepts, their relationship begins. ITNY’s skaters embraced Villella’s ideas wholeheartedly.

Cover photo of the ITNY’s website is Edward Villella’s Reveries

Then he adapted the fourth act of a Miami City Ballet piece he choreographed, The Neighborhood Ballroom, into The Three Smokers. It was done to “Back Bay Shuffle” by Artie Shaw and his orchestra: Jazz Age dance, white gloves, black tie, and pizzazz.

The Three Smokers will open an ABC television special, Shall We Dance on Ice, which will air Saturdays Feb. 21 and March 7, from 4:00 to 6:00 PM EST. He’s going to co-host it with Kristi Yamaguchi.

Photo credit: Andrea Chempinski of Scratchspin Photography

As Artistic Director, he had to convince television producers to make sure there was an arc of logic in the connections between pieces. Skaters are soloists. They come with a prepared routine, it gets dropped into an ice show shotgun-style, and the program ends up being a disoriented mess.

But that’s all people know. I was looking at the Stars on Ice comment box one night, and saw a teary eyed woman from somewhere writing about how much it meant to her to take her 86-year-old mother to this ice show, and thought this battle never began. The cultural walls between commercial sport, inexperienced audiences, and innovative art were fossilized.

I wouldn’t have the strength to deal with this, but Villella took on the job with ABC, and succeeded. He made the program one logical, artistic idea. He hopes people will see ice dance differently after watching this show.

Photo credit: Andrea Chempinski of Scratchspin Photography

I wrote an article about this special. When I submitted it to Gersh Kuntzman, features editor of the NY Daily News, he said, “It’s just not there. I’m sorry.”

“What wasn’t there?” I wondered. I worked so hard to try and fit into boxes, my body angles were skewed. But then I thought — Me, that’s what wasn’t there.

So…

For all your fights to put art first, for all the times you had to come out before the show and tell the Miami City Ballet audience what to look for, for everything you did on the stage, for all you had to endure from that farshtinkene board of directors, this is my love letter to you, Edward Villella — the greatest male dancer America has ever produced, someone who made me see the world differently, someone who has continued Balanchine’s legacy with honor.

Thank you for the conversation.

Yours sincerely,

Barbara