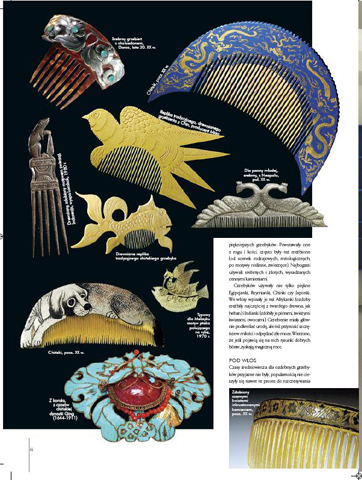

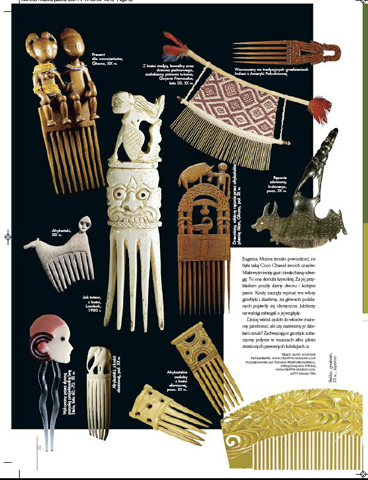

The Creative Museum was featured in Poland’s Weranda Magazine. The Polish-to-English translation was done by Kajetan Fiedorowicz. (Thank you!) Both of us thought real scholarship in hair-comb history was too vast to be portrayed in a magazine article. However, here is what Weranda wrote. They tried, I guess. My favorite part was the way they photographed a small portion of The Creative Museum’s collection.

कंघी

“Combs were used to underline natural beauty, bring luck in love, and scare off bad spirits. In the beginning, fish-skeleton combs were used as bug removers. Supplied by Mother Nature, they had nothing to do with hair grooming at all.

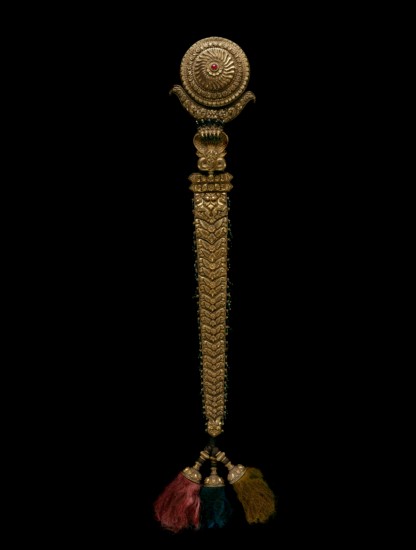

“In Ancient Greece, an anonymous first woman left a comb in her hair as an ornament out of boredom. We don’t know who she was, but her novelty was immediately noted, and a new fashion trend started. Craftsmen carved beautiful scenes on ivory and bone. Upper-class women would wear combs made of gold and silver, often encrusted with precious stones.

“In the Middle Ages, combs went back to being utilitarian. Sometimes, an inscription “memento mori” would remind one of unavoidable death. (Editor’s note: the carving art was reserved for liturgical combs, especially in France.) Most women covered their hair with headdresses.

“In the 16th Century, combs became ornaments made of expensive materials once more. They denoted social status, as did jewelry or a fan. Since a wig was able to support a heavier comb safely, their popularity allowed jewelers to adorn combs with additional precious stones.

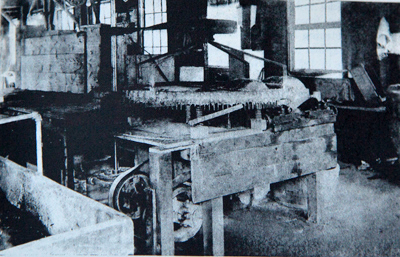

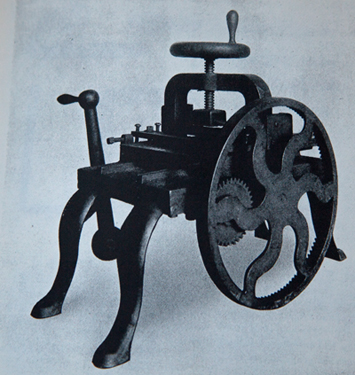

“The 19th Century brought the Industrial Revolution to comb making. In France, Germany, and in also in Poland, gutta percha and early plastics replaced expensive tortoiseshell, making combs cheaper and affordable to the general public.

“Napoleon’s wife, Josephine, known for her innovations in jewelry design, played a leading role in creating new trends in hair combs. Jewelers became very busy trying to please the queen.

“Today we have wide access to various combs. However, those truly amazing pieces are available only in museums and well guarded private collections.”