Another blog wrote about them: Le Blog de Cameline! She tells the story of the family in French. This post will be an English translation, and then I will pick some of my favorite combs from this magnificent collection, so we can enjoy both posts.

Cameline says, “The Creative Museum is a virtual museum devoted to hair ornaments.

Its history began 100 years ago, when Little Leona accompanied her military husband around the world. As she traveled, she collected treasures, which she kept in a shoe box. Upon her death, her grandchildren found the box. Wonder and passion was instantly exchanged through the generations.”

It was a moment that changed the family’s life forever. The grandchildren — thinking out of the box? (don’t kill me you guys :-) — collected over 2500 hair ornaments from all over the world and became scholars on their history. Chosen with a great eye, bought with bargaining acumen, written about beautifully, and photographed brilliantly, this collection is documented online for the world to see.

It has made its way into real museums, and the site is famous for its virtual exhibitions. The value of Leona’s passion has been realized. I cannot help but think of Emily Dickinson, one of America’s greatest poets, who hid her genius in a trunk, too, until her family opened it and had an epiphany.

Cameline chose her favorite pieces from The Creative Museum, so I encourage everyone to read her post. But here are a few of mine:

This bearded mask wears a traditional bird comb, a symbol of fertility. From the Kpeliye Brotherhood of the Senufo people, they are worn at the Royal Court. It comes from the Ivory Coast, c. 1950.

This tortoiseshell hairpin features a claw from a bird of prey. It is from North America.

This Afghan barrette dangles pendants below red and green gemstones. c. 1940.

Two phoenixes face each other in this 19th Century Chinese jade comb.

English Art Nouveau jewelers made this brass woman with flowers instead of feet and a crescent on her head.

In Japan, they loved ravens. The Meiji style has the drawing fold over to the back of the kushi.

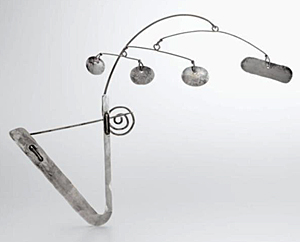

Swedish silversmiths were well known for their Minimalist style, as in this wedding tiara with pearls and tourmalines designed by Ulf Sandberg of Göteborg.

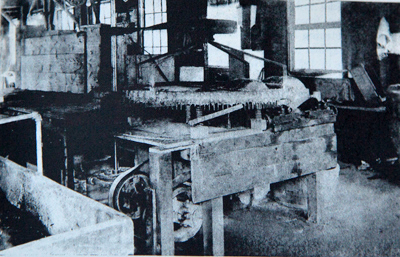

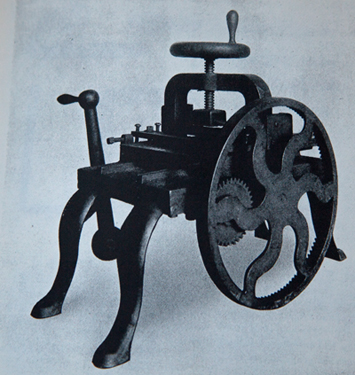

When celluloid was invented in 1862, comb-making machines lowered the cost of production considerably. In France, the industry center was in Oyonnax. Innovative design thrived with the flexibility new plastics and speed of production. This hand-painted daisy comb is a prime example of a comb made between the Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods.

Completing our world tour is a stop in New Guinea, where ancestor worship was predominant in the culture. From the Keram River area in a Kambot village comes this bamboo hair pin.

कंघी

For more scholarly research, please examine the publications of the Creative Museum, as well as these books, which can be found in our Resource Library.

The Comb: Its History and Development |

Le Peigne Dans Le Monde |

Tiara |